Betye Saar

Author and poet Ismael Reed described Betye Saar this way. “Betye Saar is as much a part of our landscape as the Pacific, the Watts Towers, the sequoias, the Golden Gate Bridge, the missions, Fisherman’s Wharf, the old mining town, the Hollywood sign, the colors of our desert and sunsets.” She was born during the Depression and learned to work with her hands—to make things at an early age and to collect items so that she had material to work with. She was the first internationally acclaimed black artist from America. Her work has spanned over seventy years and includes assemblages, installations, paintings, collages, prints, and costumes.

The objects she finds highly influence Saar. As she says, “I recycle things that I find. It’s not only materials, images, and objects, but feelings and ideas. I put them together, and they turn into an art object, collage, assemblage, or installation.” Her work is narrative, and her dominant trait is her ability to use the intimate to portray and question the collective. Sambo’s Banjo serves as a historical and political metaphor for race as performance, concealment, and survival. Inside the case with Sambo, the performer, is a slice of watermelon, a black skeleton, and a photo of a lynched black man with white onlookers. Red Signs of Transformation, which represents the historical migration of African Americans from the Jim Crow Deep South (note the crow which often appears in her work) to the north, where they could start a new life without the chains of racial prejudice.

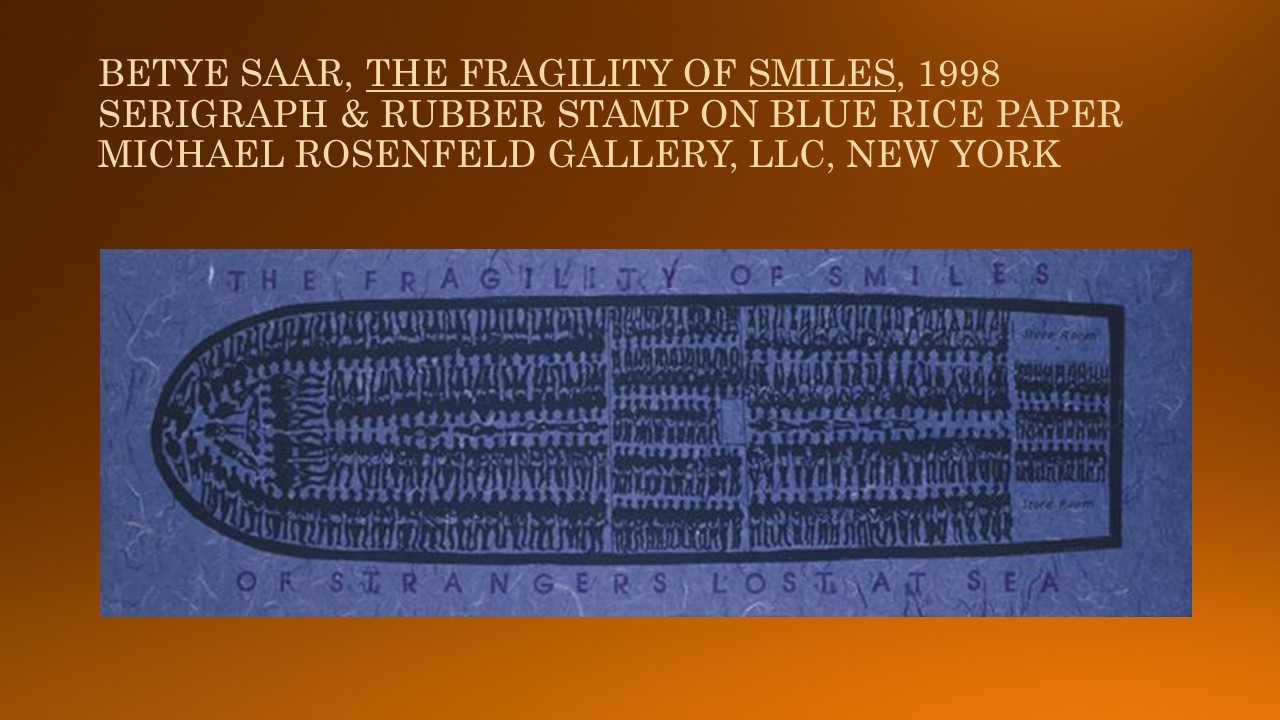

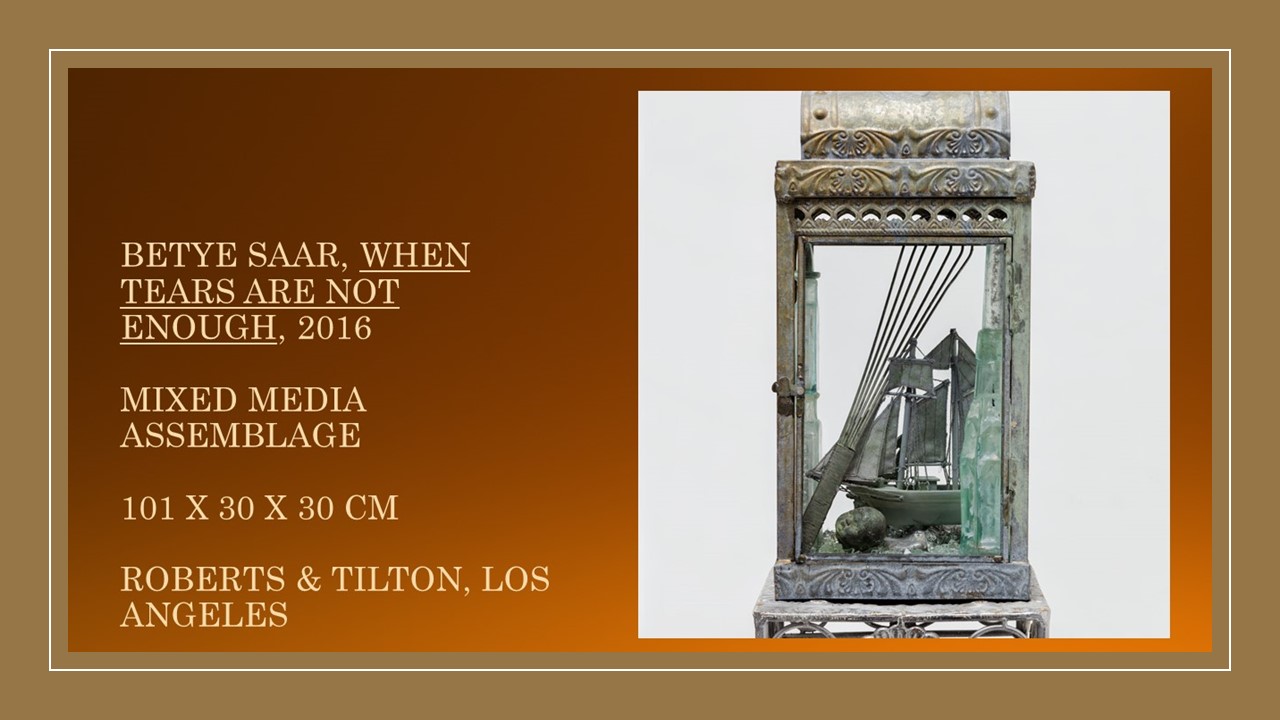

Another historical piece, The Fragility of Smiles, is a serigraph that she printed to represent the schematic placement of slaves as cargo from one country to another. In her pieces, the ship always means slave ships, as in When Tears Are Not Enough.

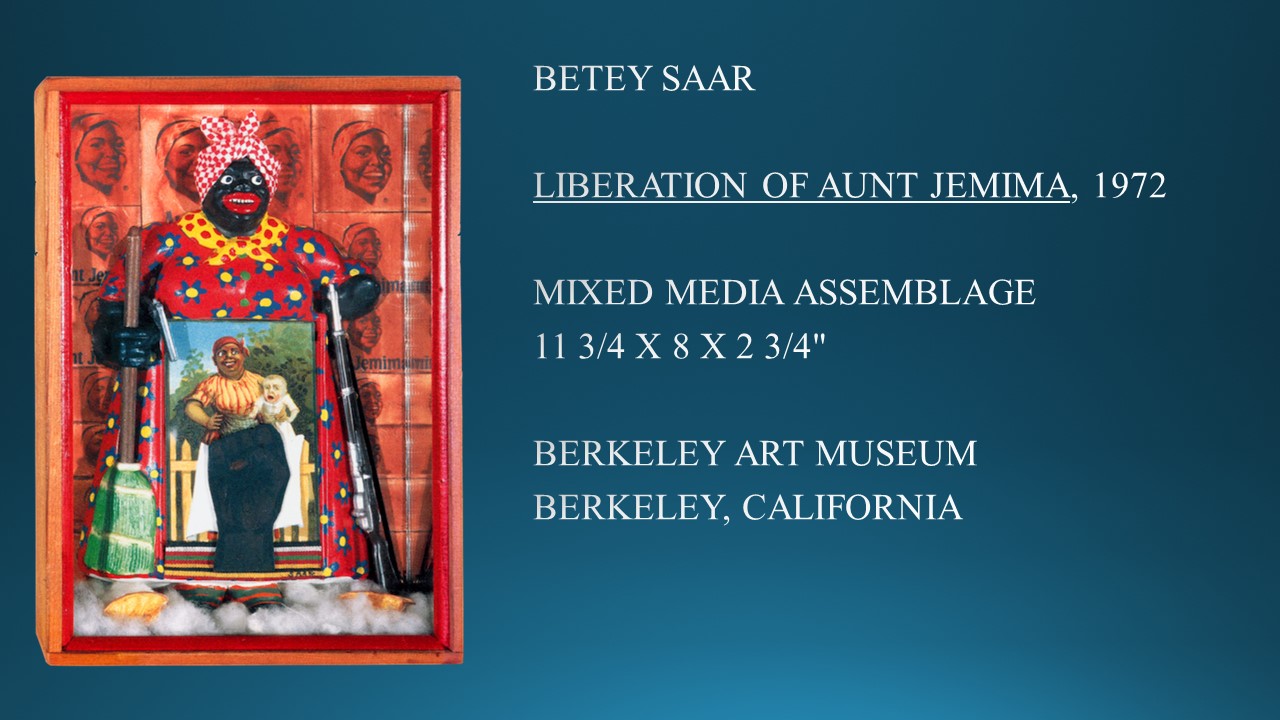

Her signature piece, The Liberation of Aunt Jemima, came about after the race riots and the murder of Martin Luther King in the ’60s. The curator asked her to make a hero piece for a group exhibition in Oakland. Saar created a heroine that would represent her protests. Her goal was to turn this negative iconography into a symbol of empowerment. Aunt Jemima was the first of her political pieces.

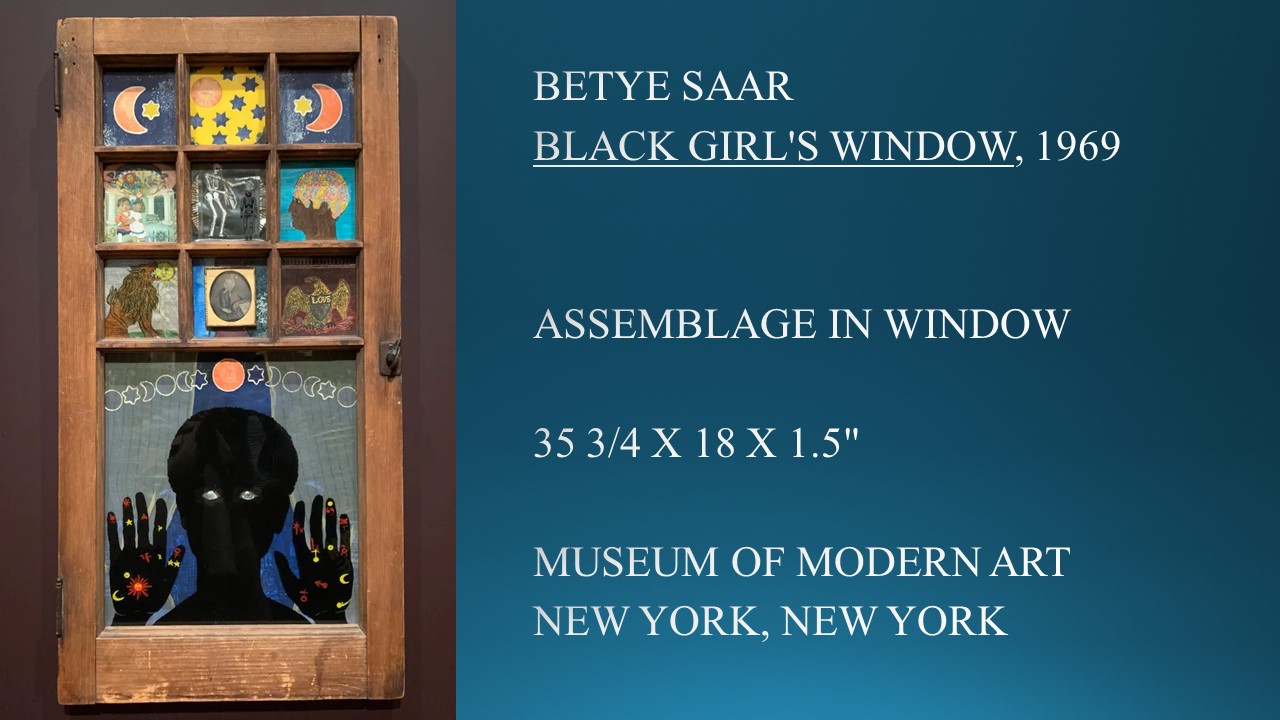

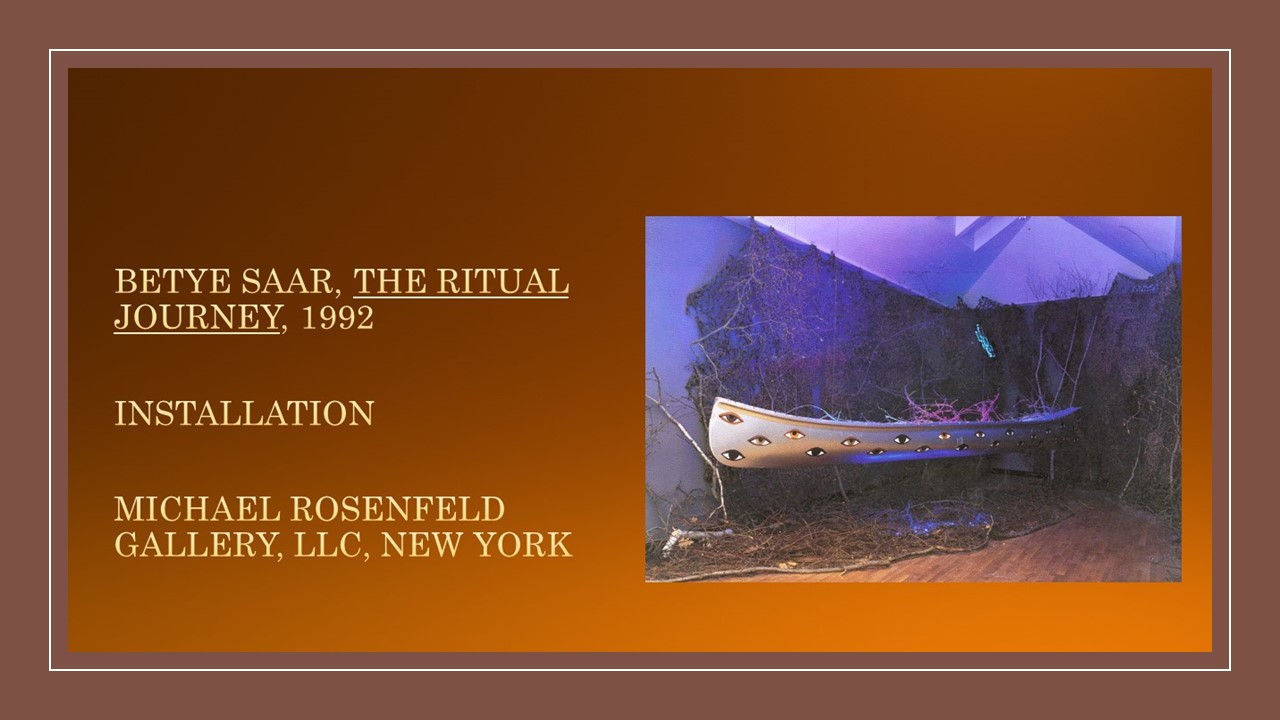

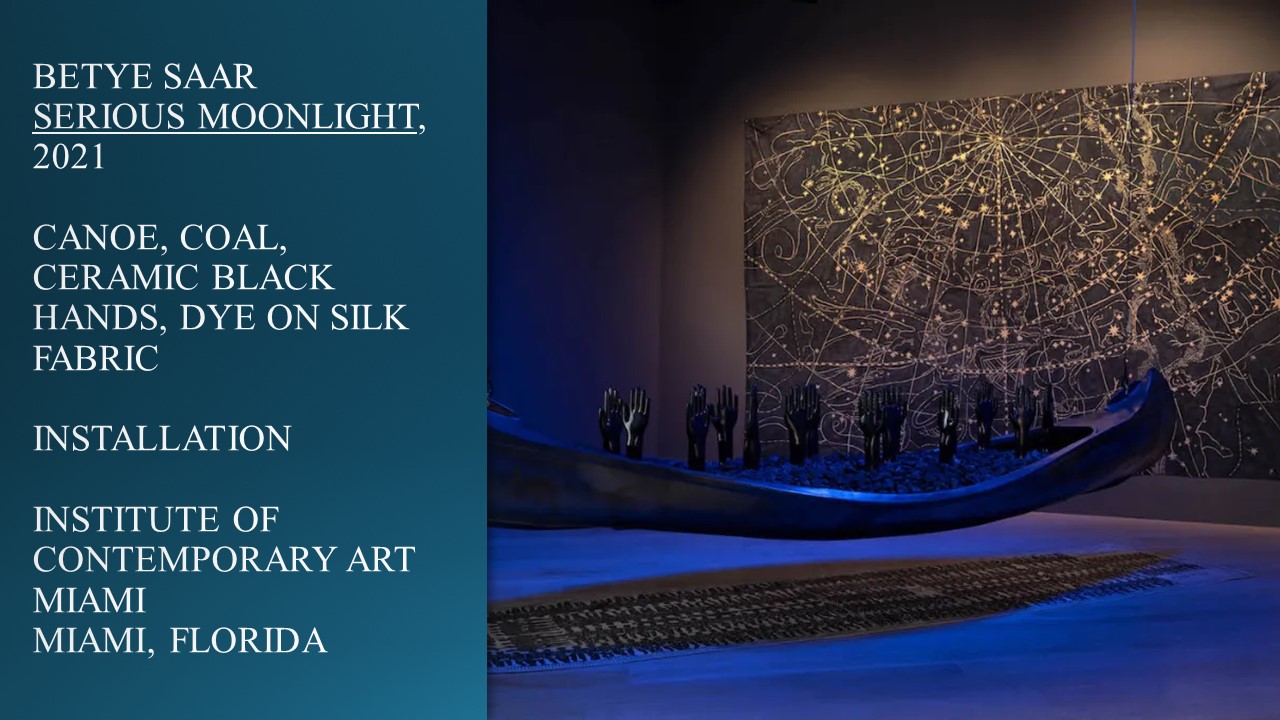

Her prior work often involved the occult, the magical, and the metaphysical; she continued to spiral back to her entire oeuvre. One of her earliest occult pieces was the autobiographical assemblage Black Girl’s Window, now owned by the Museum of Modern Art. The installation, The Ritual Journey, is a metaphor for the spiritual journey. Serious Moonlight is a tribute to the Transatlantic Slave Trade and a meditation for racial transformation.

In 2020, Saar won the Wolfgang Hahn Prize for her extraordinary achievements and influence. She always realized the power artists had to transform negative events into creative acts of resistance. She always used her art to give her audience messages. As she said, “It may not be possible to convey to someone else the mysterious transforming gifts by which dreams, memory, and experience become art. But I like to think that I can try.”

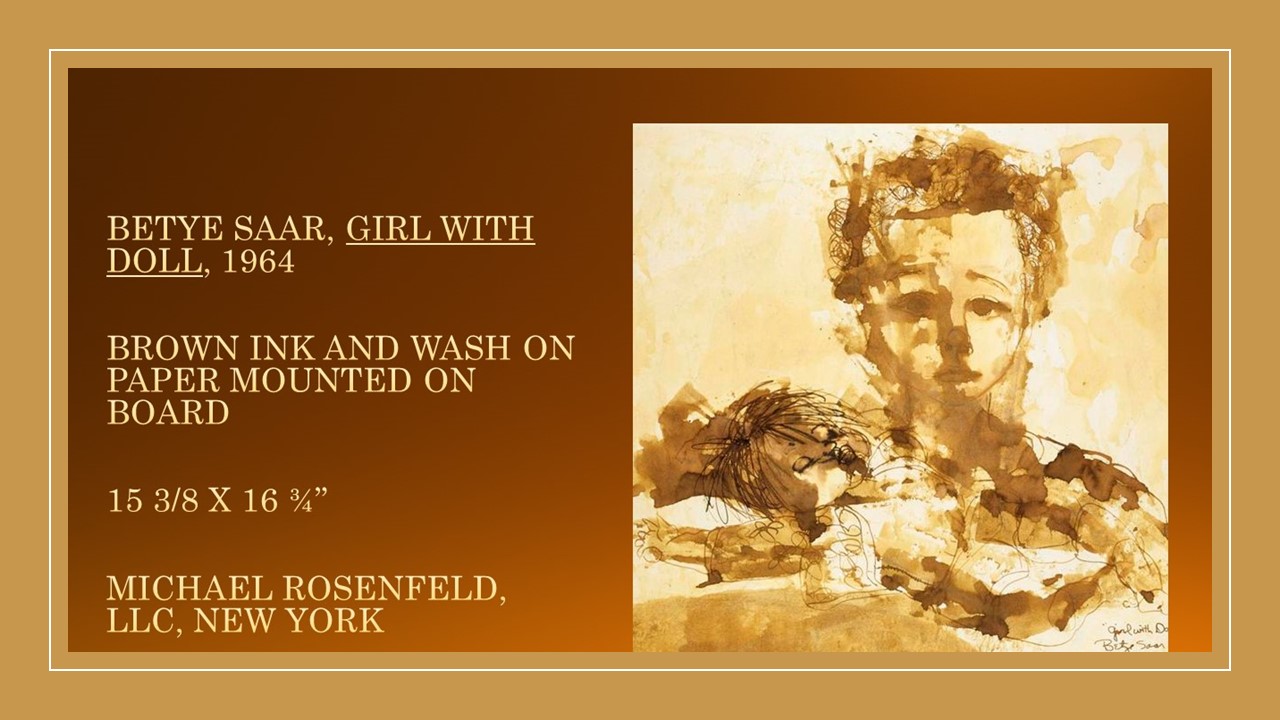

Watch her assemble Legends in Blue on the February 23, 2020, Sunday Morning interview. To learn more about Betye Saar, visit her website here; then visit Michael Rosenfeld Art and Roberts Projects to see more of Saar’s work.

PLEASE SEE PORTFOLIO BELOW