Nari Ward

Born in Saint Andrews Parish in Jamaica and immigrated to New York at twelve, Nari Ward became an American citizen in 2011. “America for me, has always been special because of its ideology that anybody can become part of the fabric of the country–the fabric of this democracy.”

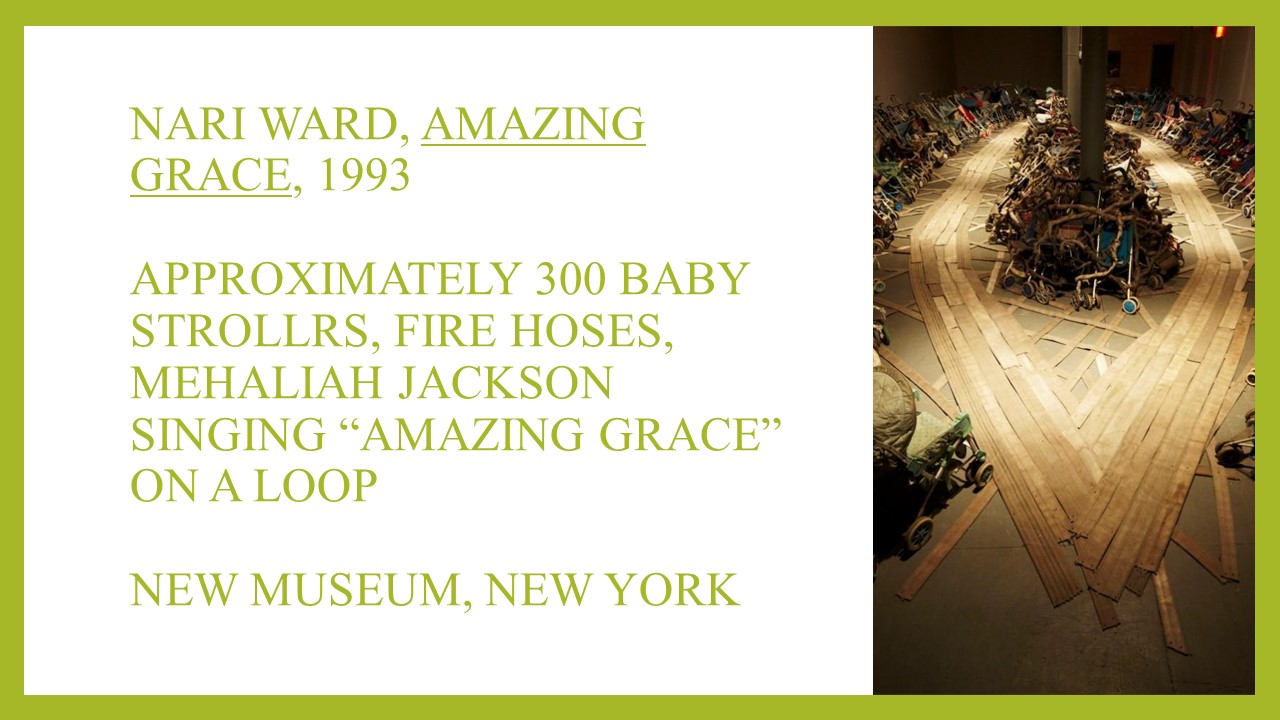

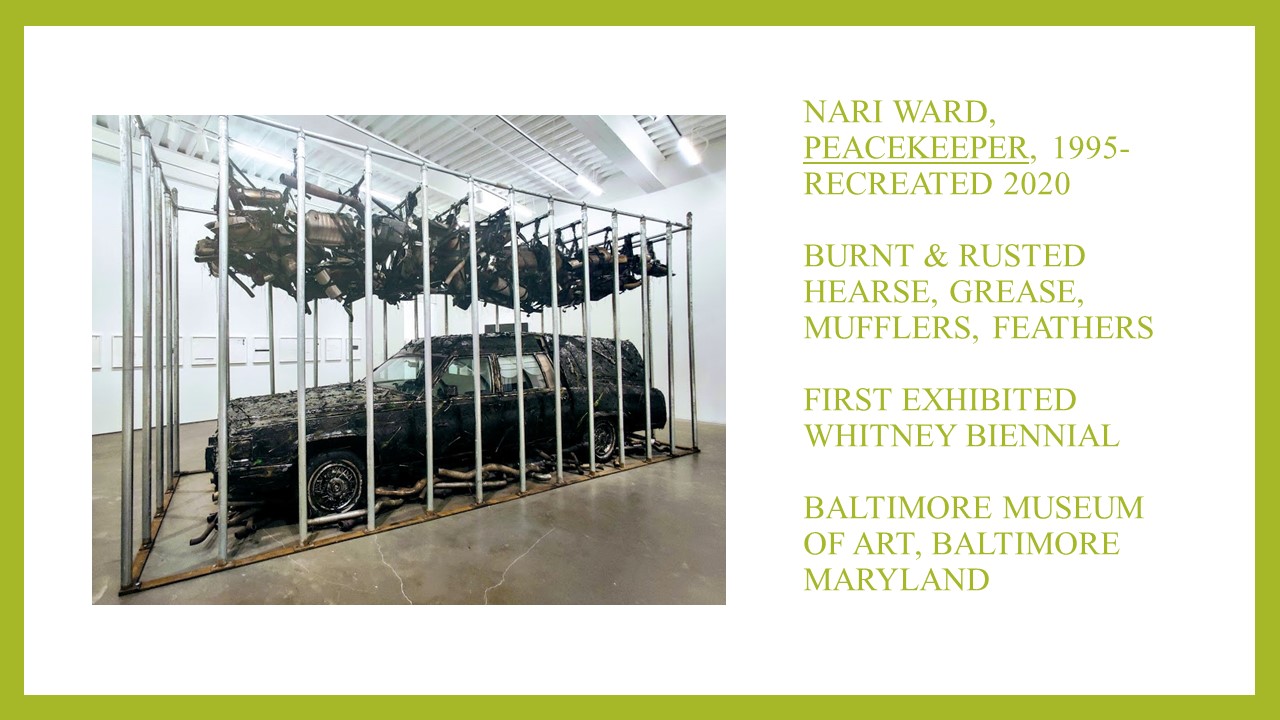

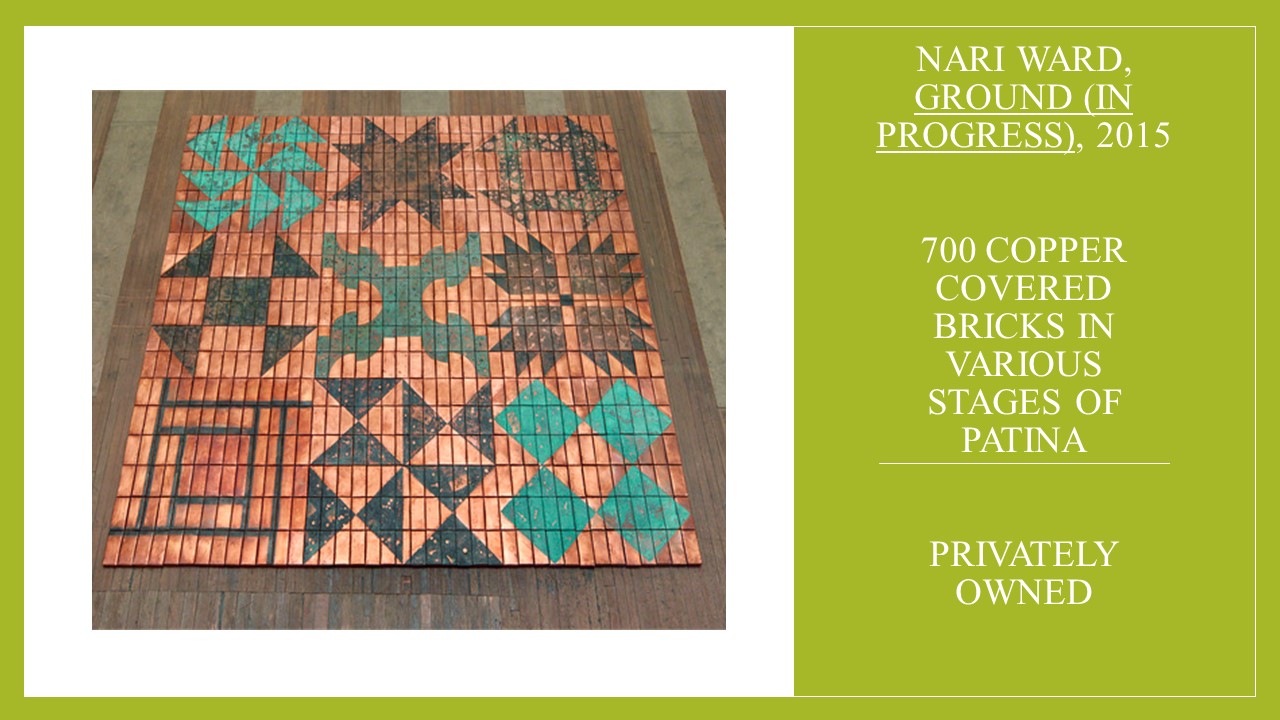

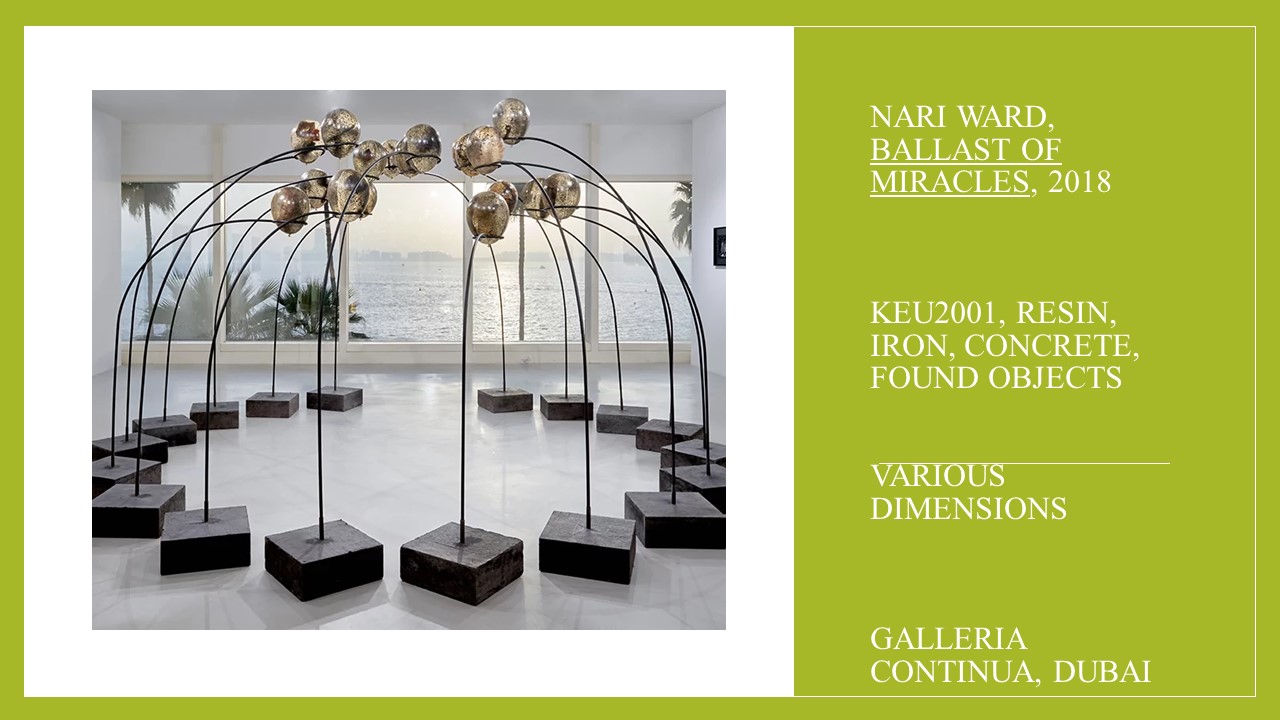

Ward calls himself a “social realist sculptor” He is a conceptual multidisciplinary artist that produces works in found-object sculptures, groundbreaking installations, performances, photography, videos, and collages. His approach to these mediums has expanded the contemporary definitions of installations and assemblages. Ward’s works reference the community, with its emphasis on immigration, cultural identity, poverty, and consumer culture. At the same time, his works speak of the power of hope within the community and strength of the human spirit.

Throughout Ward’s work, the first thing we notice is his powerful use of iconography. He is an expert in showing us the symbolic meanings in art and how they grow, lose their meaning, and change within the very culture that created them. He is a firm believer in the inseparable bond between the signifier (the artwork or icon) and the signified (the concept) itself. Because signifiers are polysemic, unpacking their meanings is complex.

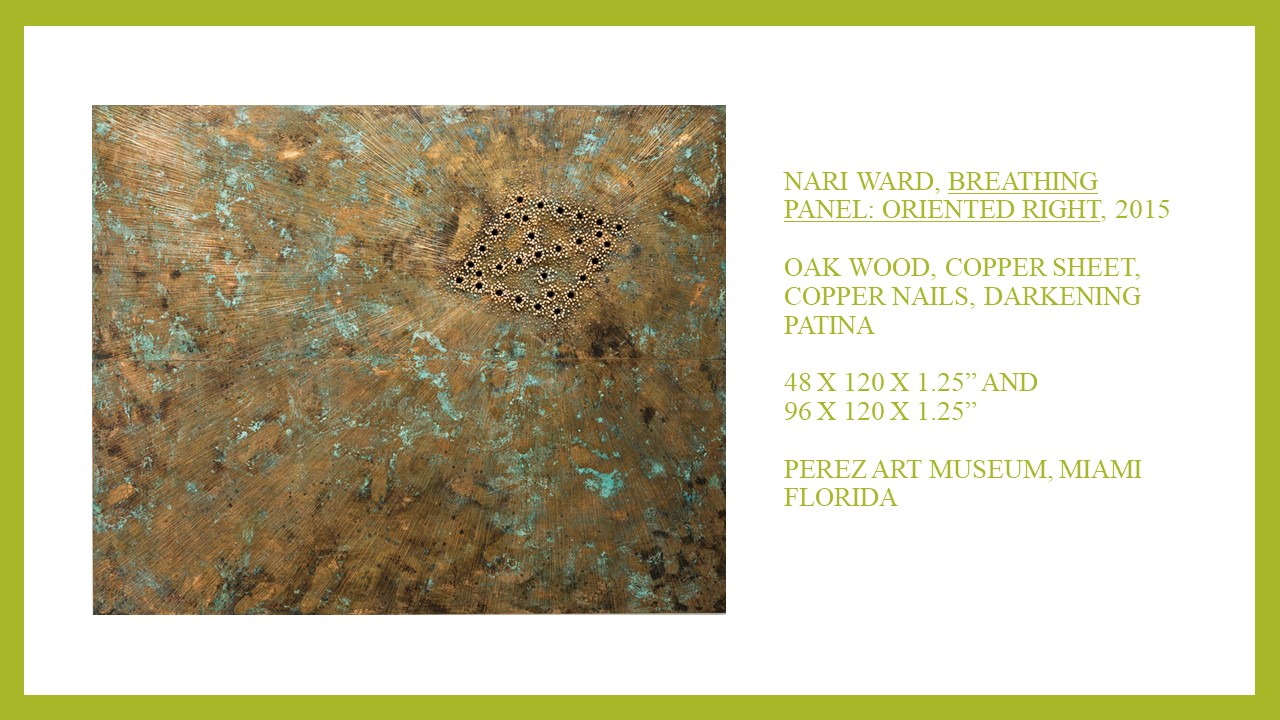

I first saw Ward’s work at SCAD Museum in Savannah. His art Spellbound included a film by the same name. Featured in the film was the First African Baptist Church built by slaves and freemen in 1777 and served as a station for migration through the Underground Railroad. The holes in the wooden floor served as breathing holes for the stored slaves in their four-foot compartments underneath. The drilled pattern was the Congo Cosmogram, indicating the spiritual voyage of souls through these worlds in the process of reincarnation—birth, death, rebirth. His works invite his audience to contemplate stories and history and to interpret signs and symbols. He always leaves the ultimate meaning of his art to the viewer’s interpretation. Breathing Panel Oriented Right was the first iteration of this symbol in a series over the years.

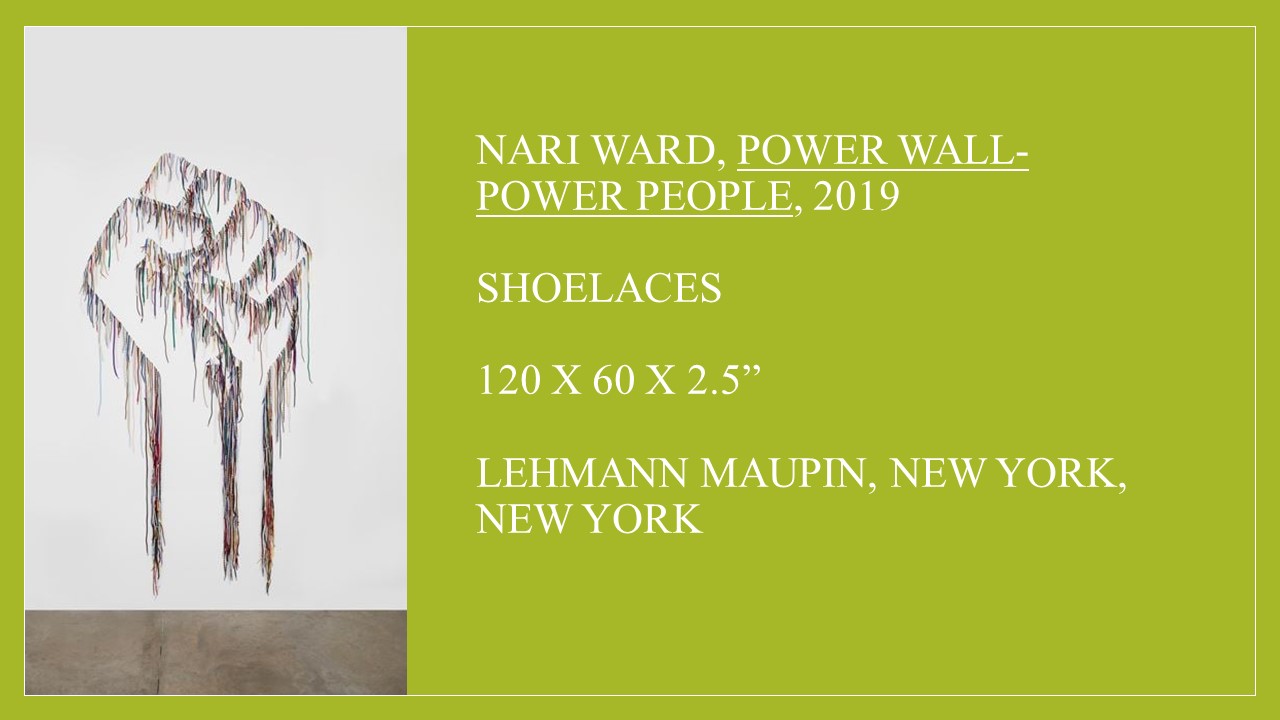

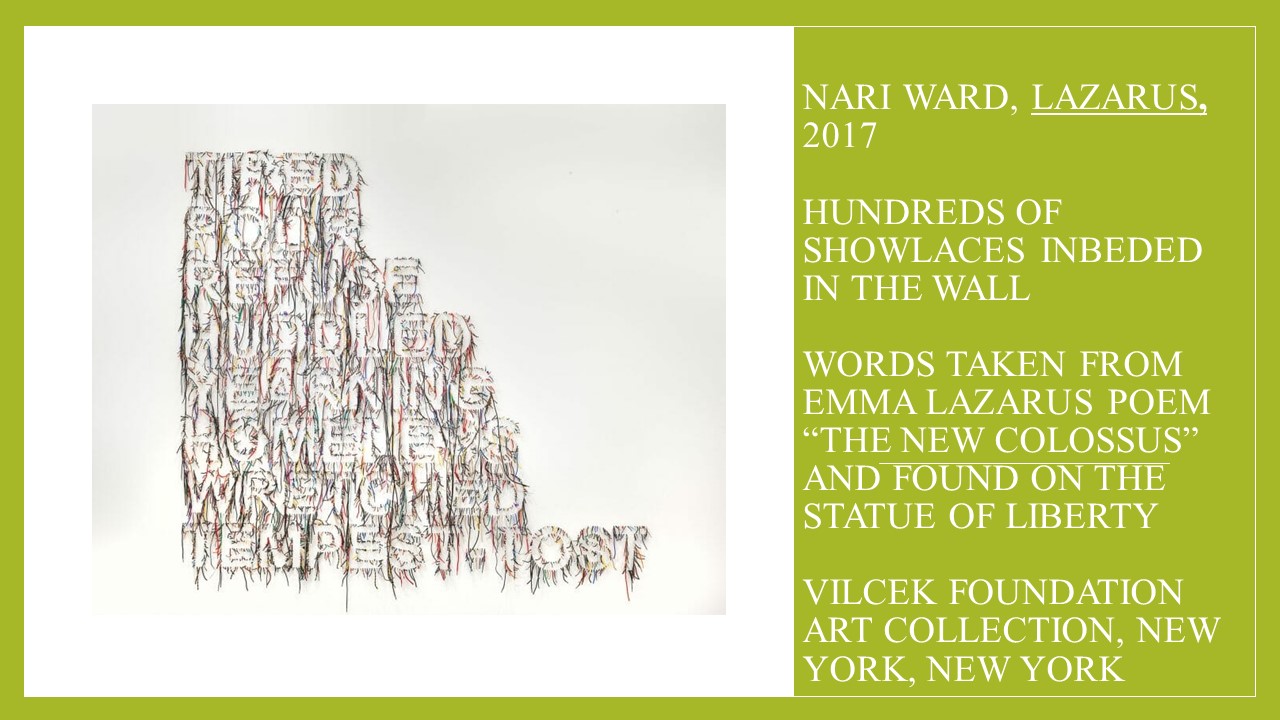

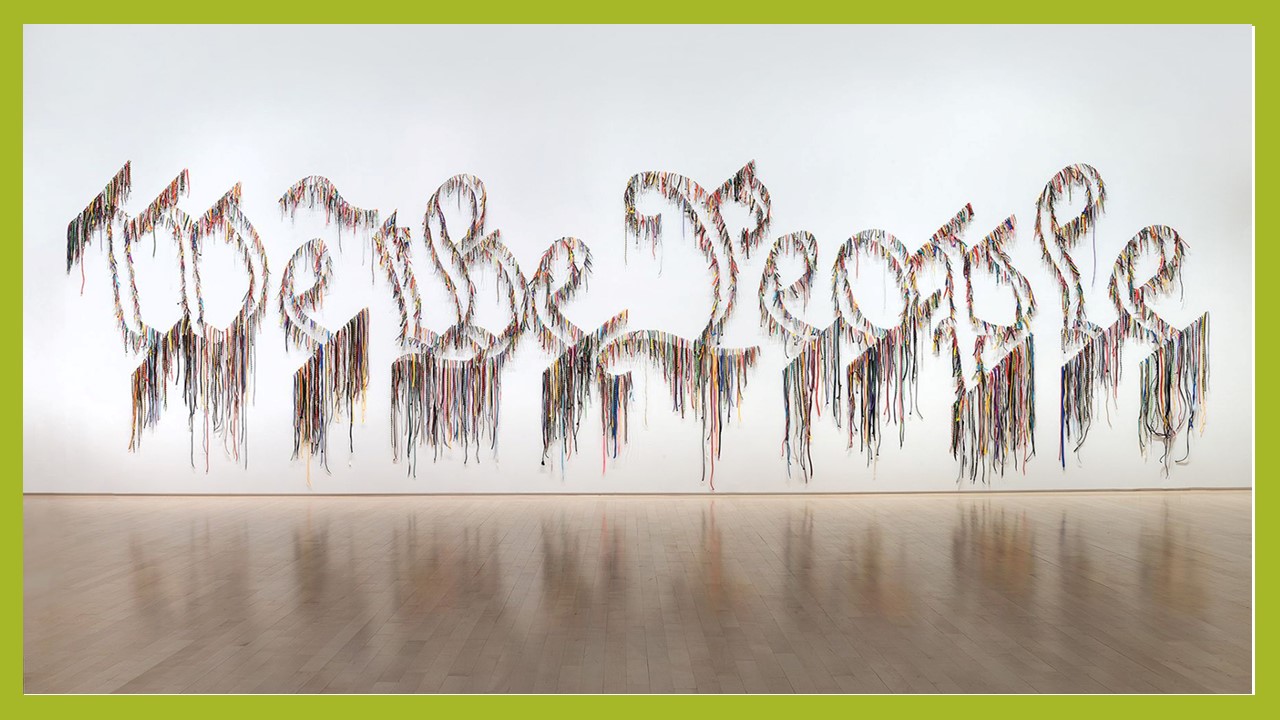

The other signifier that Ward uses often is shoelaces; used as a vernacular to speak to the ordinary persons as a community. The laces carry a celebratory aspect, as well as a mournful one—in the custom of throwing a pair of shoes over telephone lines to show a loss of life at that spot.

“We the People” bored into the walls and outlined in shoelaces, reminds us that in 1787 “people” meant only white men. The preamble to the constitution did not include women, African Americans, or Native Americans. By obscuring the words with shoelaces, the viewer must stop and think about this familiar text—he must think about what those words meant and mean today.

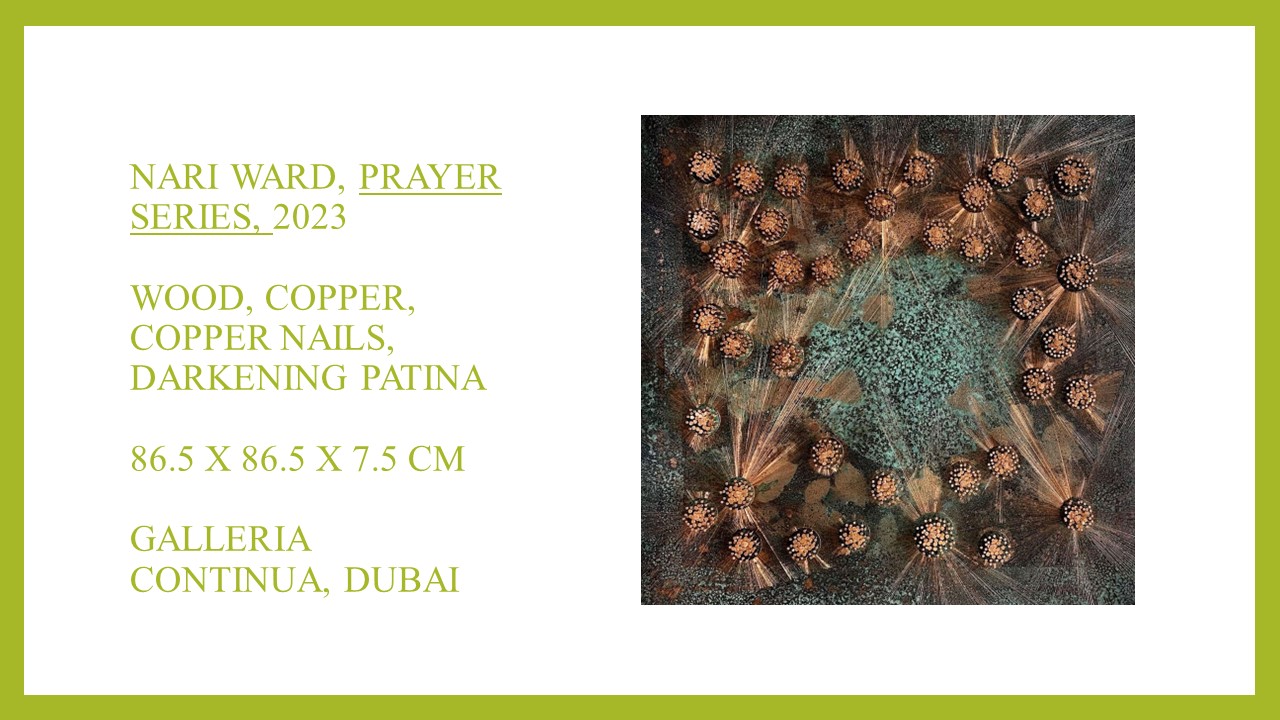

More of Ward’s work can be seen at his own website or at Lehmann Maupin Gallery, Galleria Continua, and Elizabeth Leach Gallery.

PLEASE SEE PORTFOLIO BELOW