Yinka Shonibare

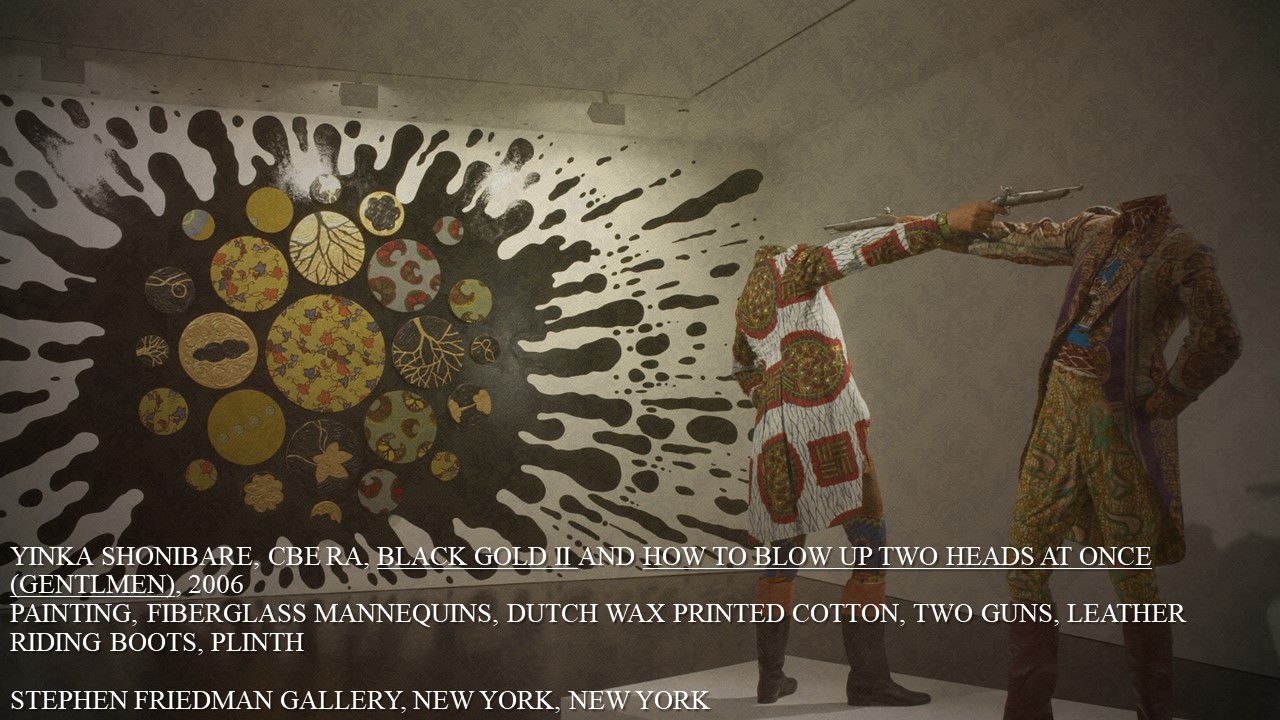

Shonibare was born in London, moved into his aristocratic family’s home in Nigeria at three years old—then returned to London to study art at seventeen. For the first time in his life, he encountered racism. One of his art teachers asked him, “Why aren’t you making authentic African art?” He knew identity as a construct was a type of fiction. His use of Dutch wax cotton identifies his work. This fabric became a cultural signifier representing a mix of cultures, like the use of the fabric itself in Indonesia, the Netherlands, and Africa. Shonibare plays with layers of identity to inform the idea of hybridized cultural identities in contemporary times. He draws our attention to this absurdness through his use of over-the-top situations using headless mannequins, or by substituting globes for heads. This takes race off the table and allows the audience to see absurdity through color, humor, and beauty. In Black Gold II and How to Blow Up Two Heads at Once, we recognize the British colonization of Africa with its politics of oil, mineral, and metallurgical extraction. In 1885, European countries came into Africa to divide the wealth of oil and left the flora, the fauna, and the rivers choked with grease and sludge thereby destroying the countryside. This condition persists today.

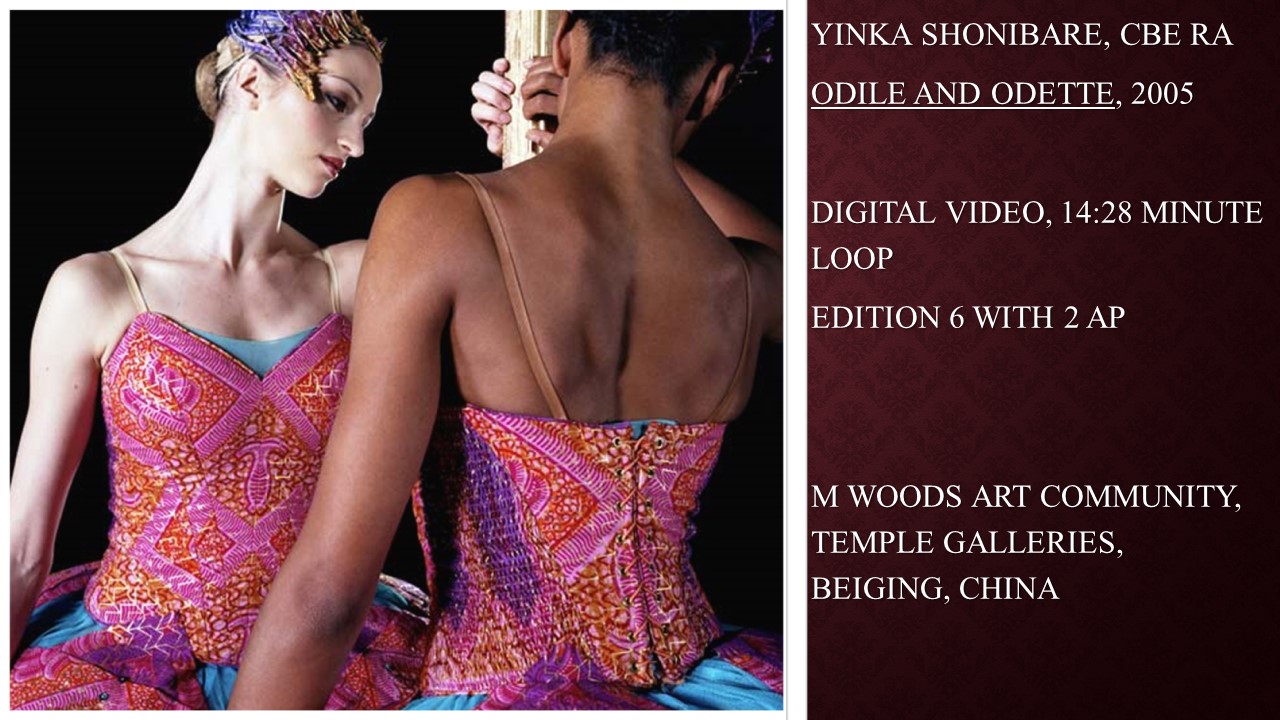

Shonibare is an interdisciplinary artist using painting, sculpture, photography, film, video, and fiber arts to show globalization through race, class, and identity. His works comment on African and European interrelationships and their resultant economic and political histories.

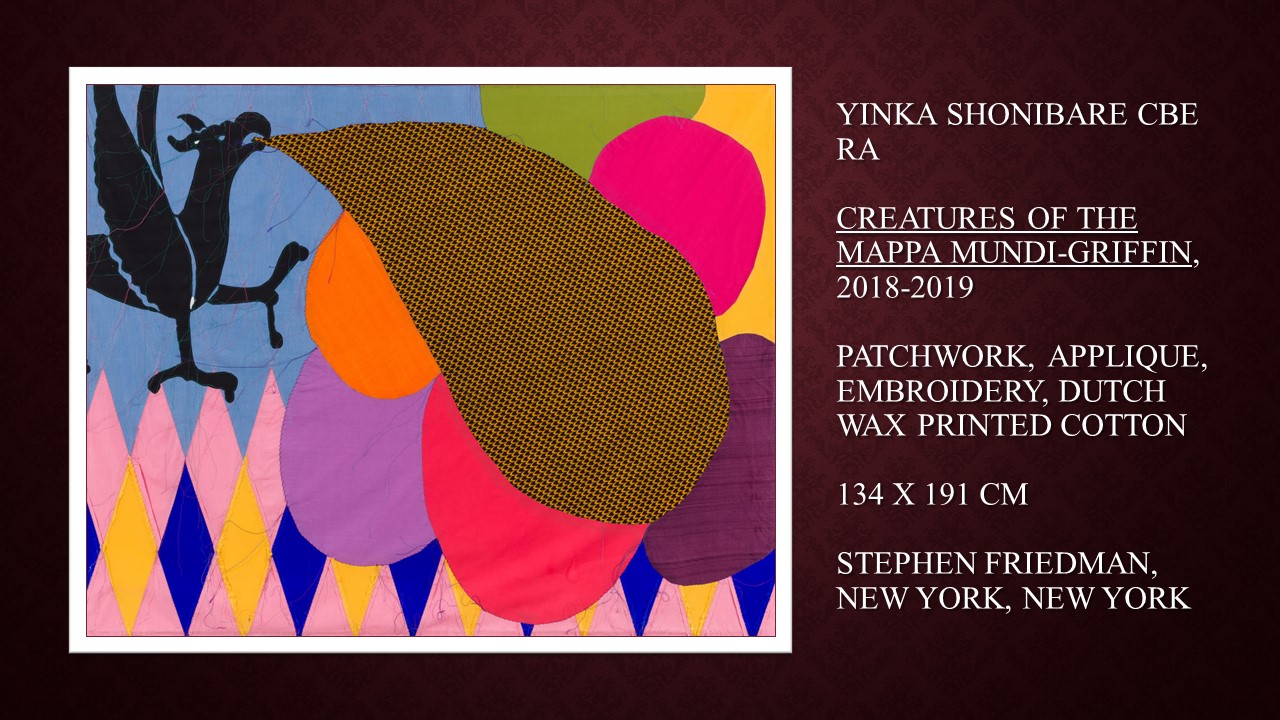

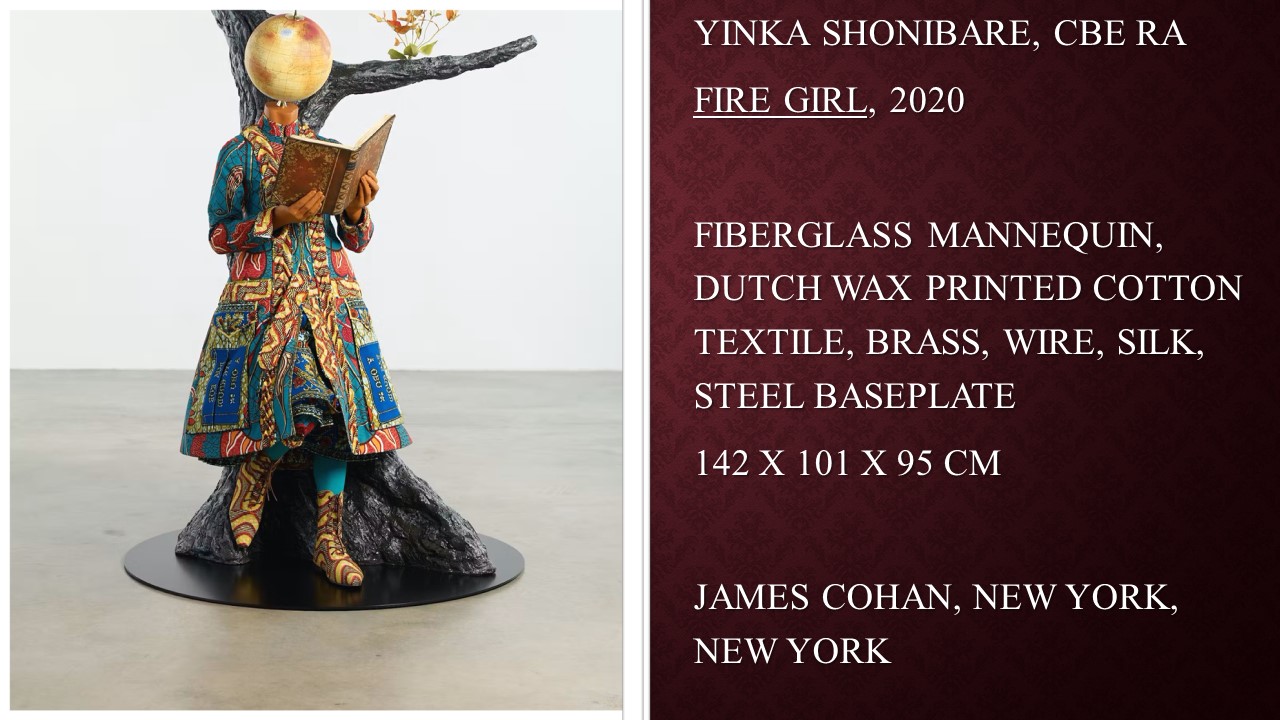

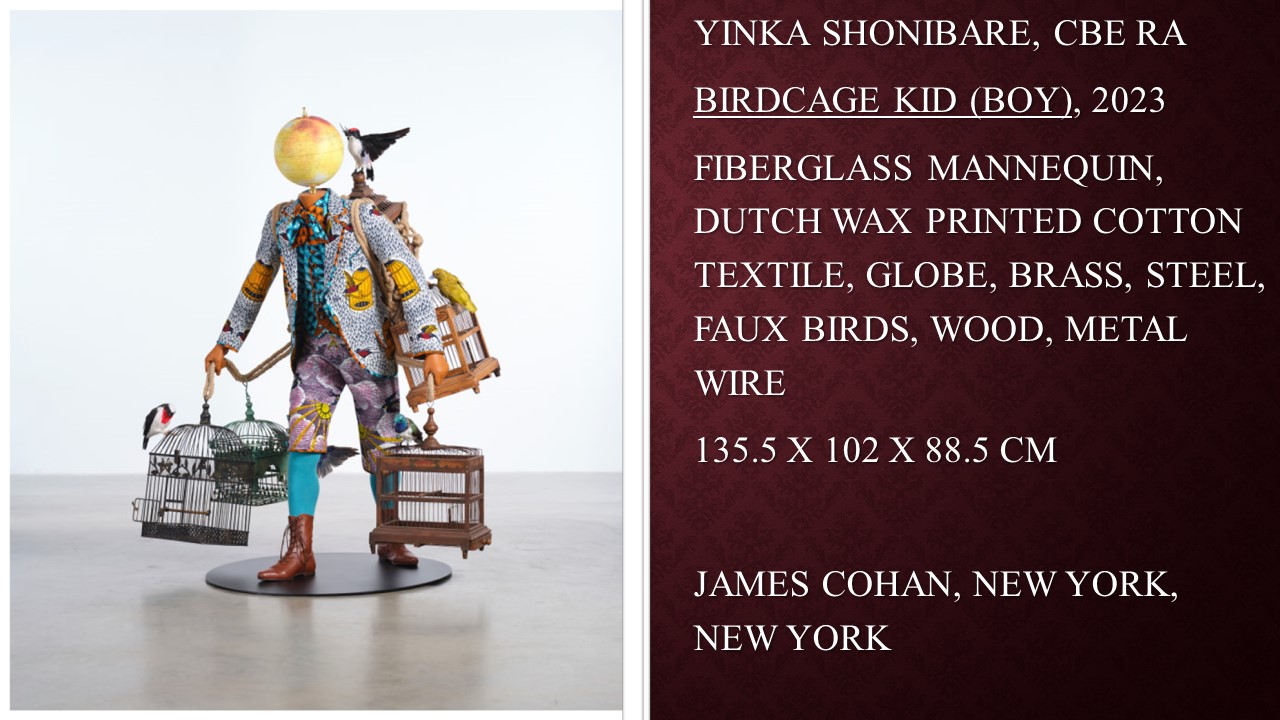

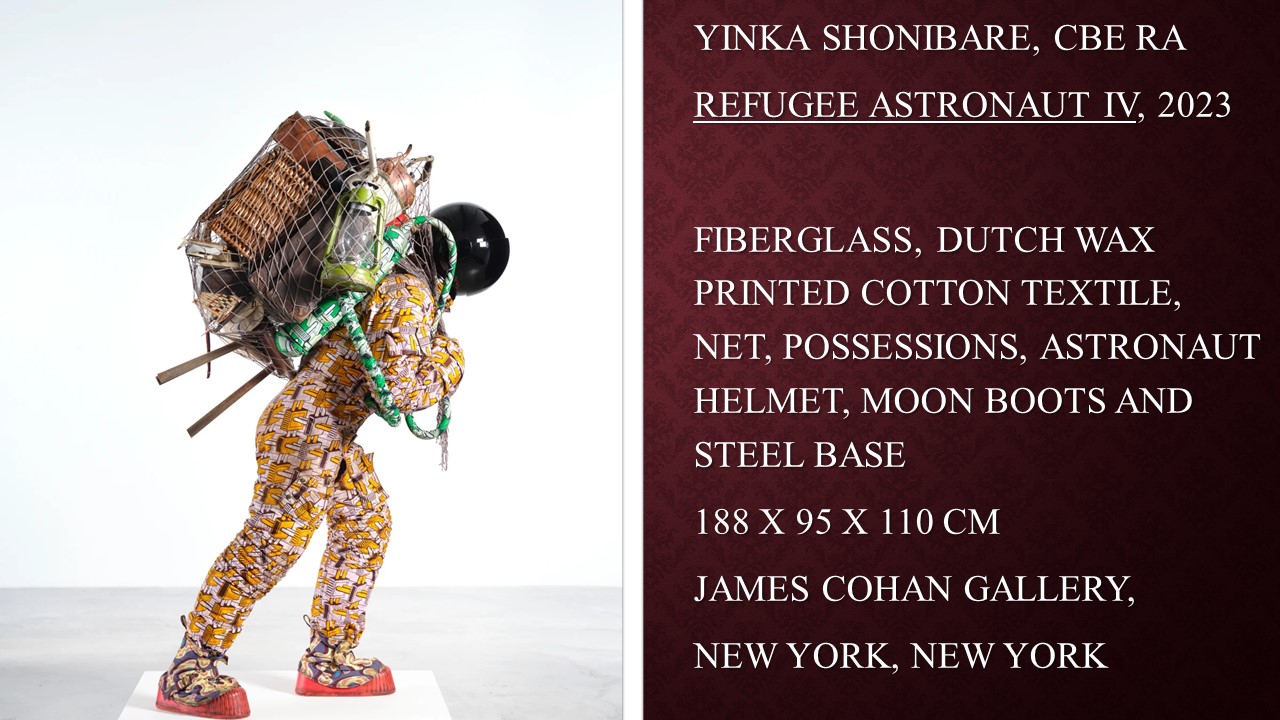

Shonibare shares two of the most pressing concerns of our times. One solution to environmental concerns is interplanetary travel to Mars and other planets as promoted by one billionaire. He suggests we migrate leaving the destroyed planet behind, as in Refugee Astronaut IV—a suggestion to solve the migration problem at the same time. The Fire Girl and Birdcage Kid (Boy) suggest other environmental concerns and serve as cautionary tales. As Shonibare was further inspired by the ability of the Medieval Mappa Mundi to still be reflecting our contemporary concerns of fear of the stranger or “other.” The depictions of extinct creatures of legend, like Creatures of the Mappa Mundi-Griffin, are a reminder that we may yet become extinct if we do not care about our environment.

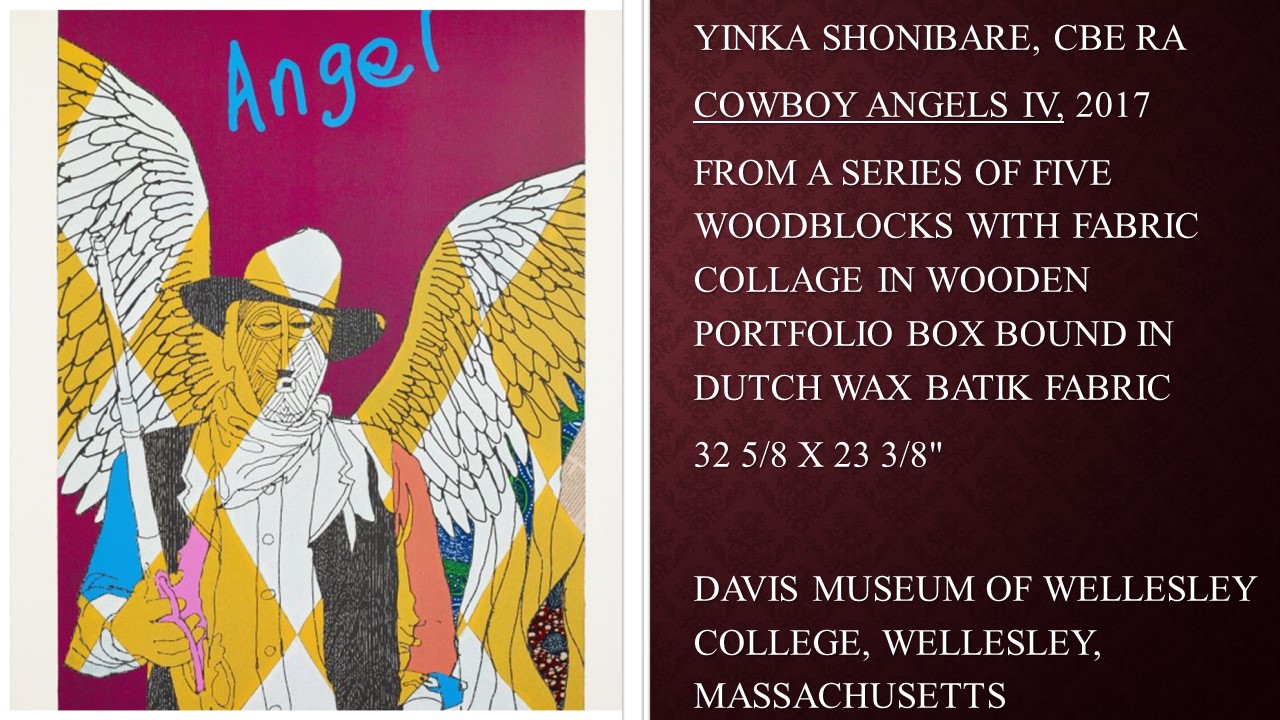

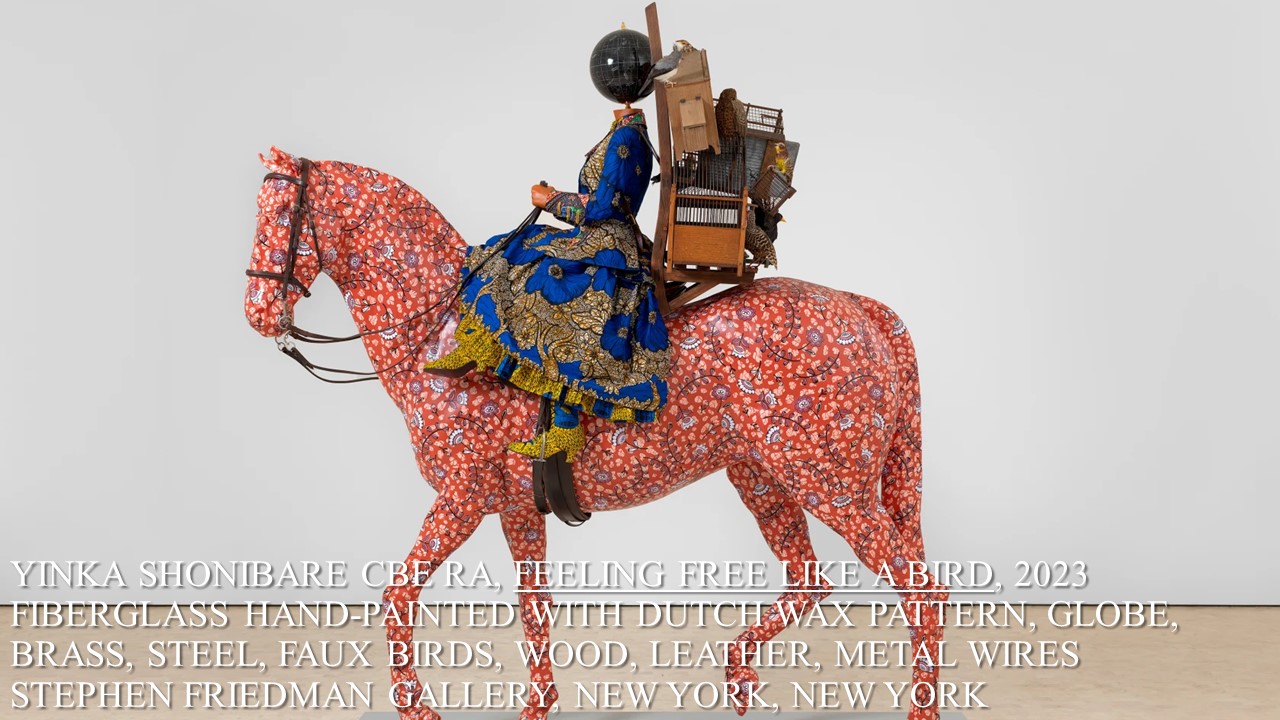

Two of my personal favorites show the resilience, the strength, and the resolve of women. Feeling Free Like a Bird and Moving Up demonstrates these leadership qualities imbued in women. Contrast these with the woodcut print called Cowboy Angel IV. Shonibare said the series was, “…a reflection on the zeitgeist at a time of xenophobia, racism, and the election of Donal Trump.”

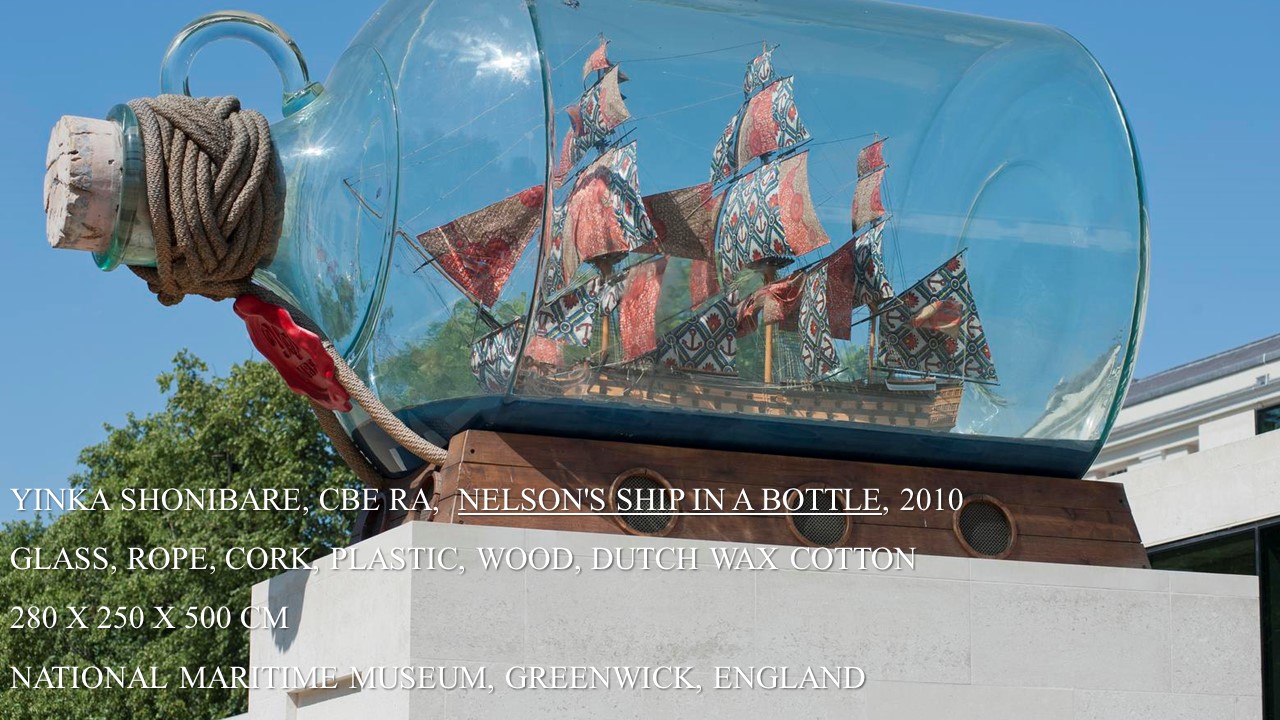

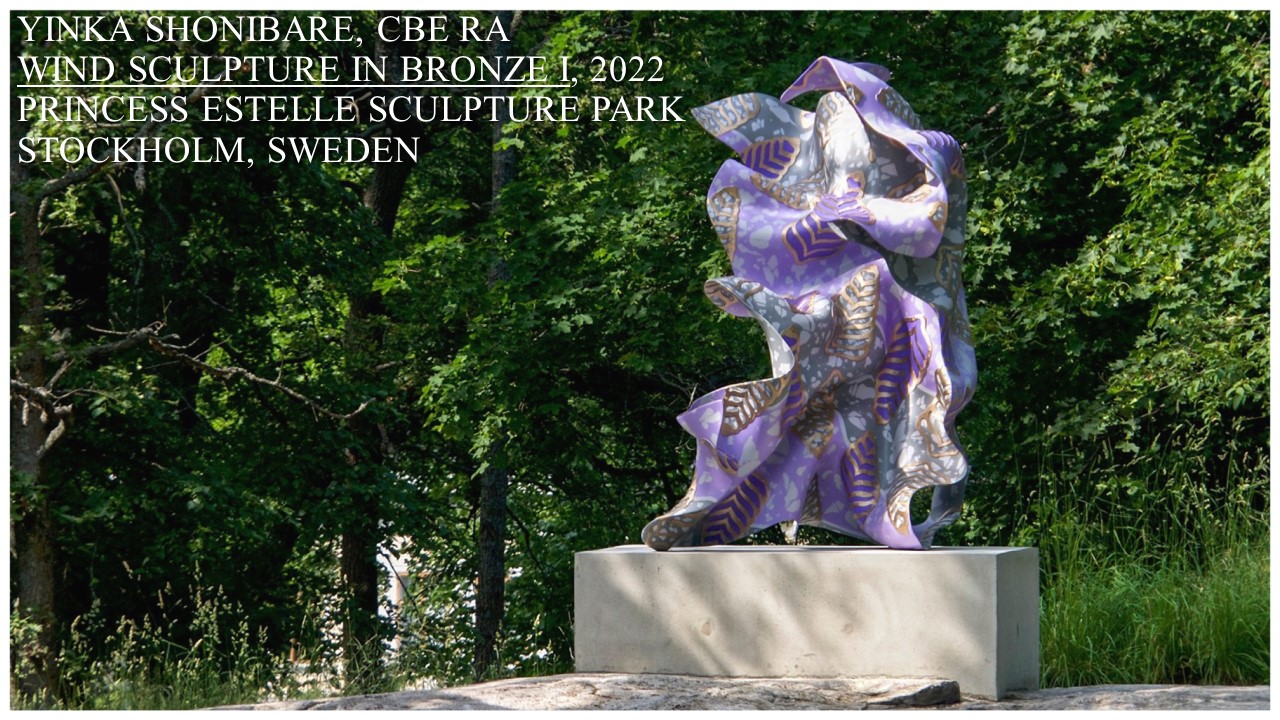

His wind sculptures, including Wind Sculpture in Bronze I, came about after Shonibare built Nelson’s Ship in Bottle. He liked the way the sails looked on their own, outside of the ship. As he experimented with harnessing the wind, he built the armature to make “the fabric” replicate the wind’s movement. He constructed the fiberglass fabric and then hand-painted it to replicate Dutch wax cotton. Shonibare’s artwork suggests “… that the opening of the seas lead not only to the slave trade and colonization but also to the dynamic contributions of Africans and African heritage worldwide”. Shonibare received the Smithsonian’s first African Art Award for lifetime achievement. His sculpture, Wind Sculpture VII welcomes visitors to the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art in Washington, DC.

View Brilliant Ideas to learn more about Shonibare.

Shonibare’s work can be seen at his galleries: James Cohan, Stephen Friedman, and Cristea Roberts. And his website.

PLEASE SEE PORTFOLIO BELOW