THE BOOK

At the crossroads of Fine Art and Zen Buddhism

ABSTRACT

Art and Zen Buddhism are only possible once the techniques are understood, and the lessons thrown away to experience them firsthand raw and unedited. Discover this artist’s journey and resurrection to a life of freedom inspired by letting go of the status quo. Going much deeper where the creative mind unleashes infinite possibilities.

My return to art school, with a concentration on contemporary aesthetic polymaths, allowed me to study these creative geniuses and to learn from them. The gifts of practicing Zen and art unfold on their own and are brought about by the awareness of living in the present moment without judgment and prejudices. Art requires resilience and Buddhism requires discipline; both result in total spontaneity with the ultimate freedom to create; to live. This natural spontaneity is instinctive, never impulsive.

As I learned to develop myself with my artwork in grad school, I also learned to write. The procedure for writing this artist’s book has been the same as the way I create my art. I begin with no preconceived ideas, no outline, and no judgments. I fill the void by sitting down to write, intending to communicate succinctly and truthfully. As the work develops, there are glimpses of ideas that motivate and guide my research. I learned to master this skill once I learned to respect and trust my intuition. This guidance led me to research and to solve complicated problems and create something original by tapping into the universal mind. It was not until I set pen to paper that I understood concepts that had been incubating in my subconscious for decades.

Art patrons like Neil deGrasse Tyson understands the artist’s need to create and to share. As he explained his favorite painting, Vincent van Gogh’s Starry Night,

It’s got swirly beautiful colors. It’s certainly not what he saw. The sky has never looked that way. But it’s definitely what he felt. And for me, an artist’s task, their duty in this world is to show me the world as I do not know it. Take me some place, give me a perspective that will broaden my interpretation of reality.

… It’s less about the making of art and more the being who you are and being able to express yourself so that others will know who we are. It’s about the reverberation and the recognition of the same reverberation inside all of us.

… Just as we are all literally made of stardust, the universe is within us. All humans share kinship with the cosmos. The reason we are special is because we are all the same, not because we are different. 1

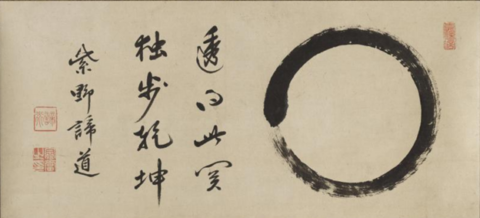

Figure 1.1, Taido Shufu, Enso, 19th Century, Minnesota Institute of Art

Chapter One

Personified Zen

When I returned to my hometown, my friend Abby welcomed me with the experience of a lifetime. She introduced me to Len, who had returned from a trip to Japan, where he had studied under a Tea Master for six months. He offered us an informal Tea Ceremony, a Chakai, at the gazebo in Whitfield Square. The Japanese Tea Ceremony developed as a transformative exercise. It dealt with the aesthetic of Wabi-Sabi, expressing conscientiousness through mindfulness and Omotenashi. Each time guests are served in this custom; it reinforces the values of honor and respect. The Tea Ceremony is the birthplace of Omotenashi.

After the service, we retired to Abby’s home, where we continued our discussion of his studies in Japan and his daily discipline of Buddhist practices. Len had an ineffable smile and a serenity that added to his authentic presence and his awareness. He exuded an open self-respect that allowed a comfort in the here and now. This state allows us to observe our thoughts, feelings, and sensations objectively. This objective self-identity allows us to avoid self-criticism and judgement while identifying and managing difficult emotions. Living with an objective ego encompasses both awareness and acceptance. I had met no one like him with his wisdom, happiness, and unconditional kindness.

I was on a personal pilgrimage to find my true nature, thought of Len’s demeanor, and learned the philosophy of Zen. A few months later, I was in New York on a business trip and met Len at his restaurant on the Lower East Side. I told him I wanted to learn everything about his Buddhist practice. He handed me a book written by Shunryu Suzuki named Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, and said, “You should begin here.”

This book defines the Zen mind as the beginner’s mind (Shoshin) and emphasizes the goal of returning to it and then maintaining it throughout Zen practice. “The mind of the beginner is empty, free of the habits of the expert, ready to accept, to doubt, and open to all the possibilities. It is the kind of mind which can see things as they are, which step by step and in a flash, can realize the original nature of everything.” 1 We recognize this term, also, as the universal, innate, and creative mind.

When I thought of this description, I recalled the feelings I experienced each time I held my newborns. Both arrived with a hyperaware condition of openness to everything. They had minds void of analytical or critical aptitudes. Both depended on an instinctual knowingness to communicate discomfort and an instinctual recognition to communicate love. I perceived each of them as authentic with a deep peace I no longer recognized in myself—matters my personality had buried long ago. They were born egoless and had a spirit that was solid and transcendent. Newborns show an attachment to the Absolute—the eternal origin of inspiration. Neuroscientist Andrew Newberg explained this neurotheology:

Humans… are natural mystics blessed with an inborn genius for effortless self- transcendence. If you ever ‘lost yourself’ in a beautiful piece of music, for example, or felt ‘swept away’ by a rousing patriotic speech, you have tasted in a small but revealing way the essence of mystical union. If you have fallen in love or have ever been wonder-struck by the beauty of nature, you know how it feels when the ego slips away, and for a dazzling moment or two, you vividly understand that you are a part of something larger. 2

Daisetsu Teitaro (D.T.), Suzuki, a Japanese scholar and writer on Zen Buddhism, recognized Zen as a pure, unmediated, individual-driven wisdom. He interprets this inner wholeness when he said, “The ultimate standpoint of Zen, therefore, is that we have been led astray through ignorance to find a split in our own being, that there was from the very beginning no need for a struggle between the finite and the infinite, that the peace we are seeking so eagerly after has been there all the time.” 3

We socialize children away from Shoshin. As the egolessness drops away, the child redefines himself as separate from his caregivers and the demands of his environment. With this, intuition subordinates itself to the self-centered perception that functions within dualistic terms. He limits his range of possibilities and thinks in Aristotelian logic—absolute terms of right and wrong/ black and white. As he develops rudimentary self-control, he gets caught up in terms of punishments and rewards in a rigid world view made up of rules and norms. As institutional socialization continues to demand more and more, the ego continues to develop, and he finds himself as part of the limited status quo, instead of the unlimited universal mind.

Psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi said,

… the normal state of mind is chaos. Without training, and without an object in the external world that demands attention, people are unable to focus their thoughts for more than a few minutes at a time…. it follows random patterns, usually stopping to consider something painful or disturbing. Unless a person knows how to give order to his or her thoughts, attention will be attracted to whatever is most problematic at the moment: it will focus on some real or imaginary pain, on recent grudges or long-term frustrations. Entropy is the normal state of consciousness—a condition that is neither useful nor enjoyable. 4

Taking care of our minds is crucial to the further evolution of the human species, not only for our own sake, but from our position of stewardship to this earth. Daily meditation is awareness and is the gift we open to ourselves by working with the chaotic mind. It gives us the ability to connect to our inborn gifts of openness, joy, and creativity. Through meditation, we learn to bypass the ego and access the wealth of qualities and information in our innate mind.

After further study of Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, the idea of mindfulness intrigued me. I was a multitasker, scheduling every minute of the day. As I trained myself to be conscientious—focusing on each task, moment by moment—life slowed down, and I enjoyed confidence in my ability to do any job well. But trying to make rapid extraordinary progress was futile and breaking old habits proved arduous. It wasn’t long before I fell back into my old patterns, as my ego gained ground and living became stressful again. I kept the book by my side and studied it repeatedly.

After I finally learned to meditate, I understood how analytically programmed I was, made obvious by the comments that ran rampant in my perception and the credence I gave them. These reflections brought their own collection of sentiments with them and set up their own field of consciousness. Meditation isn’t an immediate overall cure for being unaware. It took months of meditation until the egoic debates ended on their own, and my brainwaves settled into calmness so that I could get in touch with my core consciousness. Through focus and reflection, I directed my awareness toward the present. By doing this, I could acknowledge my egoic beliefs as they came up, and I set them aside. This opened a space of freedom where calmness and creativity could grow. In meditation, the pituitary gland kicks in and releases dopamine, serotonin, oxytocin, and endorphins for natural highs. It is for imperturbable composure that we practice Zazen. Buddhism is not the goal of Buddhism; liberation is. Buddhism is the journey to enlightenment—the existence beyond suffering—beyond the physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual.

Jon Kabat Zinn, professor emeritus at the University of Massachusetts Medical School and author of sixteen books on the neuroscience of consciousness, tells how we break from this vicious cycle of depressive rumination. Meditation allows for a wiser connection to reactions. Zinn said, “When you cultivate awareness, what you are doing is adding another dimension to the picture. You are not trying to fix anything to go away. You’re expanding the field of awareness to hold your observing capacity as detached from what is being observed. When you see you are not your conclusions or your emotions, then you have a whole pallet of different ways to be in relationship to your thoughts or emotions.” 5

As I continued practicing meditation daily, I realized intuition guiding me and offering me other alternatives. Early one fall morning, I was meditating as I did every day before the sun rose. Afterward, I walked my Bichon, Kristopher, through the squares downtown and caught sight of a distraught man. “Please help me,” he called out. “My name is Alex, and I lost my best friend last night in this neighborhood.” I told him where I had walked and that I had not seen his pet. He stopped me dead in my tracks when he told me, “I spent the night at my beach house and had a dream to show up at this corner and ask for help.” As he said this, I felt my ego step aside, as it does in meditation. To my surprise (and his), I asked him to follow me. Using the guidance I felt, we walked to Factor’s Walk, and I instructed Alex to call his dog. Within seconds, his small friend ran up the stairs from forty feet below on River Street and jumped into his owner’s arms.

The surprise shocked both of us and we wept. Still shaking, I turned to walk toward my house when I heard Alex call out, “Please come to my antique shop, and we’ll have a glass of wine”. As I arrived home, I was still in shock, humbled, and grateful. I wasn’t sure what happened; it was a timeless time and a spaceless space. I experienced a non-local consciousness, realizing I was a part of a much larger interconnected universe. As Martin Luther King Jr. instructed, “Take the first step in faith. You don’t have to see the whole staircase; just take the first step.” 6

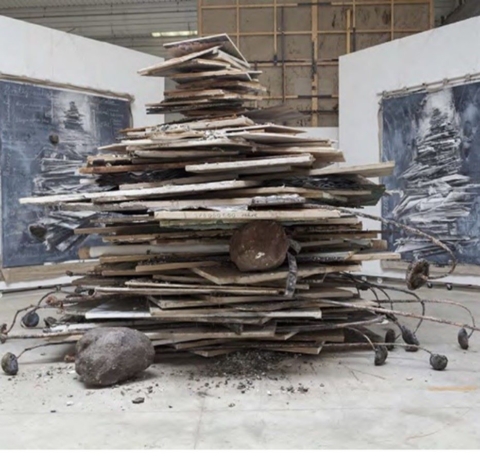

Figure 2.1, Anselm Kiefer, Ages of the World, 2014, The Margulies Collection at the WAREhOUSE, Miami, Florida

Figure 2.2, Anselm Kiefer, Athanor, 2007, The Louvre, Paris, France

Chapter Two

Art as Spiritual Enlightenment

My upbringing dissuaded me from pursuing art—I was pressured to pursue anything but that. After receiving my degree in education, I flew to New York for a week of celebration—first stop: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. While there, I found a landscape painting hung near the bottom of a wall in a corner. The exhibit label marked the painting Untitled, and the artist was unknown. As I stood in front of it, uninvited tears rolled down my face. I experienced a metamorphic transformation from the future teacher I was, into the artist I was born to be. When I arrived home, I applied for no teaching positions, but methodically planned my first art-based business.

I spent my lifetime as a creative entrepreneur and lifelong learner. For over four decades, the only constants in my life were my Zen practice and love for Art. At sixty-five years old, I returned to college to get the degrees I had always wanted, a BFA and MFA.

Both the practice of Zen and the practice of art teach self-awareness. As an artist, the more you know yourself, the better your art. The more you practice Buddhism, the more you know yourself and the better you know human nature. German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche believed the arts influenced evolving man. He considered it to be the highest expression of life and the highest form of self-expression. He argued artists show high autonomy with their right to self-govern and with their rejection of limited societal norms—the status quo. Nietzsche called them rebels who dared forge their own paths by expanding the realm of the collective unconsciousness. Authentic artists do that by translating what is yet unimaginative, but senses their works are precursors to formulations of philosophy and thought. Artists are riddle sensors and problem solvers.

We don’t know why art is worth a fortune, but we know they are spiritual objects. The spiritual unknown (both to the artist and the audience) shines through the masterpiece. Artists contend with the unknown through their open personality, their curiosity, their absolute necessity to create and their innate need to find answers. An authentic artist’s true job is to know himself beyond his subjective ego. His innate mind allows him to use his conscious and his subconscious minds in tandem. His connection with intuition allows communication from the superconscious—The Absolute.

Art critic, art historian, and Catholic nun Sister Wendy Becket, describes spiritual art as having the capacity of drawing us in deeply. “It’s going to deepen our awareness of things that matter. It’s going to make us more of a person of integrity—truer to our own essence. It’s like meeting a great genius. Being in the presence of such a person makes us feel enriched, enlightened.” 1

Sister Wendy said that spiritual art takes us beyond religion. It takes us to uncharted realms beyond our egos and beyond other entrapments of belief systems. So that, when we return to our cages [our egos], we know it is not all there is to life. Art allows us to change our perspective—to get beyond depression, worry, and constrictions. As she said, “All great art is spiritual, but not all great art is sacred. Sacred art is the most intense communication of personal truth confronting your [the viewer’s] personal truth (as much as you allow it to). So, you return to yourself enriched by encountering the Master’s Vision.” 2

Because spiritual art is enough to change our lives, it is worth engaging with all of it to realize the difference between it and art made with the subjective ego. It is important to study art and to buy it. It will open your eyes to the transcendent. We need it in our lives, because we think of ourselves as finite and bound by our own ignorance, by our own ego. It takes time to transcend the status quo and move into the divine. It involves stumbling to find your way around.

One of the hardest jobs for an artist is to learn a lifetime of technique and experience, let it go, rediscover self, and produce that same art in its simplest form. It is the concept, the quality of thought behind the piece, that is important. Art is communication between the individual soul and the divine. Connoisseurs come to appreciate the conceptual aspects more than the visual aesthetics.

As psychologist, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi clarifies in his book, Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, “[Works of] art that I personally respond to… have behind them a lot of conceptual, political, and intellectual activity.… The visual representations are really signposts to this beautiful machine that has been constructed, unique on the earth, and is not just a rehashing of visual elements, but is really a new thought machine that an artist, through visual means and combining his eyes with his perceptions, has created.” 3

#

While visiting Art Basel Miami, my daughter and I took a side trip to see the Martin Z. Margulies Collection. His acquisitions proved to be deeper and broader than most of the museums I visited. I found Anselm Kiefer’s spiritual art especially compelling. Born of the same generation, his messages echoed my understanding and my feelings of urgency. I stood before his work, in complete silence—in reverence. Anselm Kiefer is the embodiment of Art itself—everything he touches turns into Art. And his mind is a universe where conflict and contradiction resolve through his creations. As he describes it, “The artist’s responsibility is to do his work as precise as possible. What I like to do is transform things. I don’t know from the beginning what it will say. It has to be in a conversation with me.” 4 The resultant art lands outside the traditional boundaries, in ambivalent territory and it shows no regard for genre nor dominate discipline.

In a room all to itself stands the seventeen-foot sculpture, Ages of the World, 2014, (Fig. 2.1). It’s part totem, part funeral pyre, and refers to the planet’s evolution, the aspirations of art, the poetry of ruins… the cyclical nature of time. The physical elements, ash, lead, concrete, textiles, boulders, old photographs, sunflowers, and painted canvases are resonant, and Kiefer’s ordinary tools. Encircling the work makes it interactive. We become part of this evolution, part of the epochs. It is very personal as we realize the illusory belief that what we say and do only affects today. The world’s history is our history and what we do and think drives this evolution. Amidst the chaos are the dried pregnant sunflowers rising from the ashes and offering us hope of a death and rebirth. And it speaks of the desire to become something better than what we are; to learn the lessons and never repeat the horrors of cruelty and the devastations of war.

Kiefer is the alchemist that makes the invisible visible and the impermanent human condition acceptable as a work in progress. He is one of the world’s premier artists with works in almost every museum, accolades, and awards from all over the world. In 2007, the Louvre commissioned him to make a permanent installation; the first since Georges Braque, fifty years before. Kiefer created Athanor, 2007, (Fig. 2.2), which offers a key to interpreting his work.

This sacred self-portrait shows Kiefer lying in a state of deep meditation in the shavasana position. The name Athanor shows his body is acting as a philosophical furnace used to provide uniform heat for alchemical purposes. Within the philosophers’ stone, the process of transformation takes place, resulting in the transmutation of matter—either to turn base metals (like lead) into silver or gold or as an elixir of life useful for rejuvenation or immortality. The transmutation produces both enlightenment and heavenly bliss.

Kiefer describes this painting and his process this way: “Memory and forgetfulness are paradoxically related—that’s how it is. I don’t do anything other than looking for the relationships of my life with the past and the future. Here in this painting, it is me, but not only me, this is my archetype. He is here. I am a today’s man who remembers ancient times accurately. I’m here made of everyone. My memories, my past. The future is connected with the past but not mixed up. When I paint, I make movements that seem to contradict logic: I’m going into the past and at the same time into the future.” 5

The alchemical purification of the body involves the state of spiritual integration with the Universe—Religare (Latin) is the reconnection between the human and the divine. Its purpose is to regain the original purity and openness of the soul. Until we achieve this state, we will never know awareness, wisdom, and fortitude. By reconnecting with the source, we can bypass the ego and live in a state of Mushin, as the Buddhist describes it. This is the state of purity and openness with an array of creativity at our fingertips—as it was at our birth in the innate state.

Art historian, Eleonora Jedlinska, adds, “Throughout the work, a narrative is conducted referring to the belief that it is the thought process of the artist, intensity of his intellectual search and his feelings that are equal to the alchemical process of transmutation of basic elements, transition from one state to another. A work of art is therefore the bearing where the metamorphosis takes place.” 6

Chapter Three

Metamorphosis

After years of working in my studio at City Market, I wanted to return to school and swap my BA degree for a BFA. I could dabble in even more disciplines and continue to learn new techniques. As Steve Jobs advised at a Stanford commencement speech, “Your time is limited, so don’t waste it living someone else’s life. Don’t be trapped by dogma—which is living with the results of other’s thinking. Don’t let the noise of other’s opinions drown out your inner voice. And most important, have the courage to follow your heart and intuition. They somehow already know what you truly want to become.” 1

Although a degree is unnecessary to be an artist, I reported to my community college to earn the degree I wanted many years ago. To transition from a self-taught to an educated artist, I closed my gallery at City Market and registered at my community college. Since I had earned the BA, I only needed to pick up thirty hours of art and art history classes to earn a BFA equivalency.

The state of Georgia provides grants for its sixty-two-plus citizens to attend degree applicable courses for free. Armstrong was the perfect educational setting for me, as non-traditional students were the norm. Over half a million students over fifty years old enroll in degree-granting institutions across America each year. James Fallon, a neuroscientist at the University of Irvine, claims “people that are at their maximum cognitive abilities are in their 60s.” 2 The Seattle Longitudinal Study tested thousands of people over 50 years old. Its research showed that this group performed better on four out of six tests than younger adults.

Information was more accessible than it was in my twenties. The first time around, school meant countless hours in the library; this time, the internet provided information with AI pattern recognition capabilities. This volume of material at my fingertips allowed me to delve into research material quicker, deeper, and broader. Education courses, as a way of accumulating information, will become irrelevant. AI accumulates knowledge, acquires information analysis, and applies it better than we can. Information will be available everywhere, as it is now clear. By then, we must be competent to move beyond information and its application. As Elon Musk considered the purpose of things as they are today, he came to one conclusion: “If we can advance the knowledge of the world, if we can do things that expand the scope and scale of consciousness, then we’re better able to ask the right questions and become more enlightened, and that’s really the only way forward.” 3

A golden era for human society, another Renaissance, is available for those willing to grow with the coming changes. As Buddhists have known for thousands of years, tapping into the unconscious has been beneficial to all humankind through their abilities to know empathy, compassion, and lead the way out of suffering. Conceptual artists have known how to tap into their unconscious for information and guidance to create important works—significant forms of communication. Because we are all born to create, we can retrain our brains to tap into the deepest part of the mind, with its importance as the container of hidden contents and instincts. If we choose to remain untrained with the use of self-referential ego intact only, AI will take our jobs, as robotics have done in the manual arena.

As the classes became more challenging, I felt the cobwebs dissipate and the brain rewire itself. My curiosity led me to research neuroplasticity. our brain’s structure and function alter as we accept new challenges and experiences. Neuroplasticity is the most significant insight of neuroscience over the last decade. Because of the advancement in medical imaging techniques, evidence for lifelong brain plasticity has proven to be true. As Lisa Pauwels, Sima Chalavi, and Stephen P Swinnen describe their research findings, “In view of the demographic evolution of society, characterized by an increasing proportion of older people, the evidenced lifelong brain plasticity provides a critical foundation for a sustained role of older adults in society and for securing prolonged independence and quality of life.” 4

Our brains developed between 100,000 and 35,000 years ago, are the most advanced brains on the planet, and are remarkable machines. Our thoughts are the genesis of everything. We are not even victims of heredity but masters of our genetic activity, as shown through the study of epigenetics. Genes are blueprints—they don’t control our lives; they don’t even control themselves. Epigenetic attachments work onto DNA to regulate genes from birth, while new ones (epigenetic attachments) are being added, they dissolve old ones. This reversibility happens at will. Through healthy habits, we each have the potential to purge the old and supplement with new attachments. With purpose and effort, we can change our epigenome game plan whenever we choose. Whatever we think, we achieve. For example, when we express gratitude for anything (health, love, kindness, money, etc.), we are receiving nerve cells grown to receive more of those directives.

#

Because I had a lifetime of art and business experience, I found the foundational classes of duplicating reality to be a disappointment, a retardant, to creativity. I found that the art school embraced principles of western education—teaching linear thinking for accessibility and for easy testing. Instead of turning out creative thinkers, they turned out obedient followers, and yet, business leaders and economists tout creativity as the #1 thing we require for economic growth, success, and general happiness. This is the fascinating dichotomy between employment and education today. It is the artist, not the educator, who understands how to correct this difference of opinion. The art school missed the entire point of art, as defined by Aristotle. “The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but the inward significance.” 5

The convergent educational approach kills concepts and passion and is contradictory to the very rationale of creativity. Artists must become comfortable with ambiguity and vulnerability because they must remain wide open to creating from the inside out. Inspiration generates divergent ideas, brainstorming, and the re-imagination of metaphors. Artists continue to incubate thoughts through transdisciplinary research that takes them to places they could not imagine. These conceptual thinkers exercise nondiscriminatory wisdom without prioritizing the visible over the invisible, the explicit over the implicit.

It became apparent to me I was going to need to enhance the educational system itself for me to remain interested. The traditional foundation classes proved important to learn new skills and techniques using materials germane to mediums. And the art history classes were valuable for understanding the historical context. Once I understood new techniques and how to handle new materials, I could then figure out how to apply them to other materials and mediums and expand art forms. Besides the syllabus of assigned classwork, I continued to add these newly learned techniques to my conceptual work.

Artists must eventually surrender all biases, traditions, and preconceptions to enhance creative inspiration; to make it work more effectively. The easiest way for me to free my mind of limitations and expand awareness is through meditation. It causes the random chatter to quiet, my energy to rise, and gives inspiration a chance to fill my mind via intuition. It is important to be open to gut feelings; the ones we know to be true because we feel them in our body. These are the ones we do not want to doubt or dismiss. There are other ways to empty the subjective egoic mind. Einstein took power naps and went for long walks, whereas Steve Jobs meditated and went for long walks, too.

Catching sight of the muse, the aw ha moment, is the ability to hold focused attention and, through clarity, make us aware of the muse’s arrival. Sometimes intuition comes in bits and pieces, sometimes in whole thoughts. The point is to continue to show up, aware and ready for the muse to come. As Rudyard Kipling informs, “When your Daemon [ancient Greek muse] is in charge, do not try to think consciously. Drift, wait, and obey.” 6

Steve Jobs had the most creative mind of the technological revolution. He reimagined seven industries: personal computers, animated movies, music, phones, tablet computing, digital publishing, and retail stores. He describes the processes of socialization and the demand for creativity to overcome the status quo.

When you grow up, you tend to be told that the world is the way it is, and your job is just to live your life inside the world. Try not to bash into the walls too much. Try to have a nice family life, have fun, save a little money. Life can be much broader once you discover one simple fact. That is, everything around you that you call life was made up by people that were no smarter than you.

The minute that you understand that you can poke life and actually something will pop out the other side, that you can change it, you can mold it; that’s maybe the most important thing. It’s to shake off the erroneous notion that life is there and you’re just going to live in it, versus embrace it, change it, improve it, make your mark upon it. I think that’s very important and however you learn that, once you learn it, you’ll want to change life and make it better, cause it’s kind of messed up, in a lot of ways. Once you learn that, you’ll never be the same. 7

Chapter Four

Surrendering to The Path

After completing my BFA program, they accepted me into grad school, and I continued living in Savannah while driving to Georgia Southern University to attend classes ––resulting in a journey of an hour and a half drive each way for three years. I didn’t want to lose all the cultural advantages of Savannah for a culturally deprived town in Georgia’s cotton fields, and I could not turn my back on free education in an area that captured my attention. I felt driven to learn more about the creative mind and figure out how conceptual artists find other ways to express thoughts other than through the conscious mind.

Admission into grad school is challenging, competitive, and based on a portfolio of work. The student arrives knowing how to make art; at grad school, he learns to be a professional. Curriculum includes art history classes, research, art theory and criticism, professional practices, studio, and thesis work. All BFA level classes are open to the MFA candidates for further exploration.

Making art continued daily under the student’s supervision and in his or her studio. Making their rounds, professors did not show up in the workroom to pass out encouragement, support, or give instructions. Their critiques were relentless and constant. Once a month, the faculty gathered to critique the students’ work, and they insulted us in a group setting. Because they held these reviews after the monthly faculty meetings, it felt as if we were the entertainment portion of their “get togethers”.

After years of making a living by painting canvases, it shocked me to hear that I did not know how to paint. At my first critique, the professors tore down my art and yelled at me to defend my work. Confusion and astonishment overcame me as the hurled insults continued for about ten minutes. I felt as if I were in a mental institution reliving the scene from One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest—where Nurse Ratchet led the inpatients into a critique session to discuss Mr. Harding’s problems with his wife.

Higher education often teaches by tearing things down rather than building them up, and the integrity of a student is often determined by how they criticize and counter arguments. These kinds of discourses penetrate the culture at large. Critics measure their intelligence by how well they can devitalize an idea, artwork, or even a person.

Trying to wrap my head around what had happened, I went for a long hike. I knew I would not stay in school and take this kind of abuse sold under the guise of criticism. The next day, I met with the chair of the art department to discuss this problem. This was Robert’s first semester, as it was mine. He confessed he was as shocked as I was, and he promised me it would not happen again. He changed the faculty critiques to include the grad school professors only and not the entire art department. Because these professors understood our personal processes and goals, they could offer more pertinent critiques.

Michael Markowsky, professor at Emily Carr University of Art and Design in Vancouver, Canada, explains the MFA program this way:

I often discourage students from pursuing an MFA because I don’t believe most of them are ready or willing or capable of undergoing such an intense experience, and therefore it would not only be a waste of money but also might destroy their interest in making art altogether. I personally believe someone interested in pursuing an MFA should have both a very clear idea of what they are doing and want to do, and also an extremely open mind to working with people who will ruthlessly challenge those ideas. Anyone who is stubborn and inflexible won’t get anything else but frustration out of the exercise, and anyone who is lost and timid will find themselves traumatized and torn to pieces, and–as one of my former MFA advisors once said–incapable of putting themselves back together again. 1

Because I was more interested in the creative act than just painting, I researched other mediums. This allowed me to create in all disciplines while learning new techniques and introduced me to a broader array of artists. To enrich these experiences, Robert stepped up as my mentor. He taught me how to look at my work and others more objectively and ask questions that uprooted decisions about materials, mediums, and techniques. He challenged me to think—to analyze divergent thoughts and compile insights.

Looking for the most extensive way to explore creativity and to share who I was as an artist and a person; I gave installation art a chance. My background in design and love for many types of art mediums kept me open to try anything. Every element—the art objects, the venue itself, and the space in between—was necessary to tell the complete story. Because the audience walks into and inhabits the space, I considered the whole-body experience. Adding elements of light, sound, smell, and texture created a multi-sensory experience. Because it is less familiar than traditional art, the ability to shift perspectives is like traveling to a foreign place. The elements of being unfamiliar and surprising allow the artist to blur lines between art and life.

All installation art is conceptual. As Sol LeWitt described in “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art”,

When an artist uses a conceptual form of art, it means that all of the planning and decisions are made beforehand, and the execution is a perfunctory affair. The idea becomes a machine that makes the art. This kind of art is not theoretical or illustrative of theories; it is intuitive, it is involved with all types of mental processes. It is usually free from the dependence on the skill of the artist as a craftsman. It is the objective of the artist who is concerned with conceptual art to make his work mentally interesting to the spectator and therefore usually he would want it to become emotionally dry. 2

The elements in this art form build a larger narrative, giving it more importance than a painting could. It is site specific, allowing the artist to transform any space into a customized environment; thus, allowing a one-of-a-kind aesthetic experience with each visitor. This type of art engages the mind rather than the audience’s eye or emotions. It is the most intimate with philosophy—the idea constructs the art, and the idea continues constructing the reality of the observer.

In my first semester, I attempted my first multisensory installation art, named Zenside, as shown on this website under the heading Installation Art. The goal was to make a quiet meditation room separate from the chaotic outside world. The intention was to carve out a room within the row of grad school painting studios and to introduce meditation as both a way to clear distractions and a technique to intuit insights.

To begin any artwork, I spend a great deal of time researching. But because I have meditated for decades, I skipped that step. I put all my ideas about presentation on the back burner and allowed for an incubation period. This valuable time allowed me to use my unconscious mind to show me ways to show the meditation process to those who did not practice it. I wanted the audience to feel the peace, safety, and comfort of a cloistered space, much like being wrapped by a warm blanket. Illumination came as a sketch illustrating the space divided into two parts—a quiet inner space and an open outside space filled with chaos.

To flesh out this insight of being in the world, but not of it, I designed a translucent curtain dividing the spaces. The curtain allowed for light to transmit and diffuse items on either side. Evenly spaced pockets housed the malas used during meditation and gifts to be taken home as reminders. They were accessible from the inside or outside upon entrance. Each of the prayer beads was distinctive, one from the other. By touching the beads one at a time, the practitioner found his breathing rhythm and the comfort of being with himself.

Tenting the meditation room allowed light to be transmitted down into the space. The space felt warm and safe—distinctly different from the outside world. A Buddhist prayer bell hung on the drape, marking the beginning, and ending of each session by striking each time someone entered and left the space. These bells, made by master bell-crafters, make a pure resonant sound, deep in tone—reminiscent of endurance.

Inside, incense purified the air and filled the space with sandalwood. Recordings of quiet chants reverberated through the body and promoted the parasympathetic nervous system, rendering the meditators relaxed. I made meditation cushions from stacks of newspapers tied together with twine to represent our “thoughts” we all bring with us to the meditation area. The key to meditation is acknowledging the thoughts are there, but by “sitting on them,” we continue our meditation without interruption.

The focal point of the meditation room was the free-floating sculpture made of painted art tissue. These colors remind me of the energy I see in my meditations and the “clouds” of cosmic dust known as nebula.

I designed the narrow hallway to be the outside world and to feel crowded and uncomfortable. Structural necessities—exposed ductwork, plumbing pipes, electrical wiring, and exhaust fans—added to the density. Loud broadcast news bombarded the senses with unwanted noise and made the “outside world” miserable.

Newspapers hung on dowels like those found in libraries marked the exit out of this commotion. And painted lunar calendars represented how long man has studied time—from the interplay between the moon annual cycle, ecliptic, solstice, and seasonal changes on earth. Since the late Upper Paleolithic cultures, man has made time our enemy, another form of stress.

After the installation, I spent days in critical reflection to determine if I had hit my marks in considering the audience’s perspective. I took many still photographs from various angles and hired a videographer and model to walk through the space and record it. Finding various students to question my work was invaluable in tweaking any assumptions I had made.

A smaller faculty group, all grad teachers, attended the critique. Focusing on the details, they presented rational and constructive criticism. The faculty recommended that I continue working on installations as my discipline.

I became more curious and creative as I moved from medium to medium—from sculpture to painting to furniture making to ceramics. The brain always defaults to the same neural connections when we continue to stay in our safe places and take the paths of least resistance. The discomfort of moving into unfamiliar territory forced me to explore unknown aspects of myself. I usually got there through meditation, hiking, or through programming my sleep time. Once the new visions incubated and developed, curiosity led me down paths I could have never predicted. I followed them until new forks on the roads appeared; then went down those roads, too. Eventually, enthusiasm ignited the vision, and the work of art made itself. Once you can see it, you can do it.

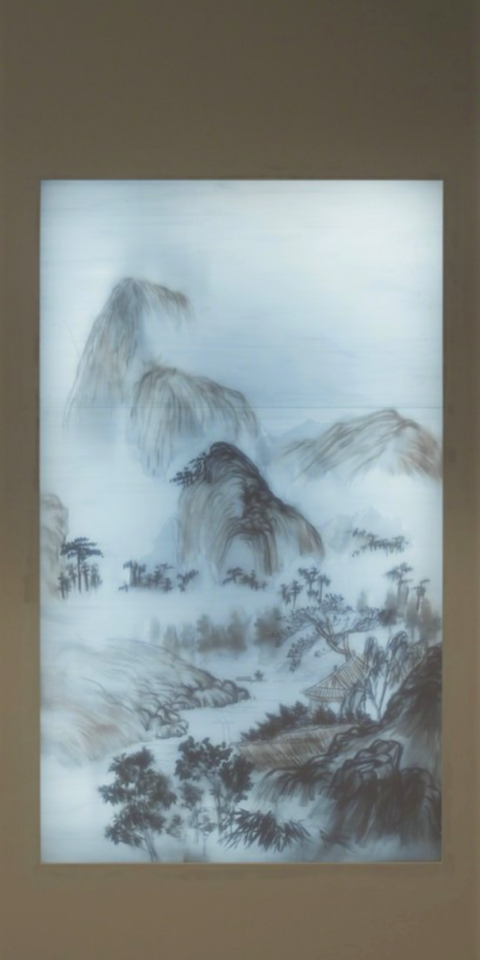

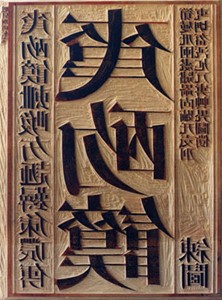

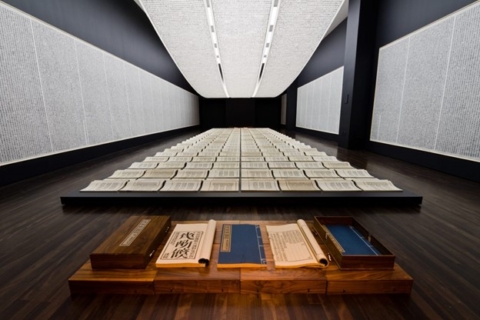

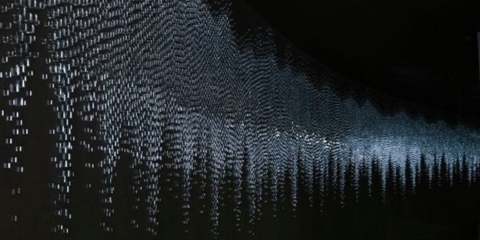

Figure 5.1 and 5.2, Xu Bing, Background Story, 2015, SCAD Museum, Savannah, Georgia

Figure 5.3 and 5.4, Xu Bing, Book from the Sky, 1987-1991, National Art Museum of China, Beijing, China

Chapter Five

The Influence of Xu Bing

I studied conceptual artist Xu Bing’s work since I entered grad school. My mentor had suggested this artist as his work reflected the practice of Buddhism in contemporary art. Xu’s art is a place to explore humanist psychology and Zen’s philosophy as avenues of communications with his audience. This makes his work universal, deep, and nuanced, resulting in uplifting experiences.

When word got out Xu was being honored at SCAD, we rushed to see his work in person. This Song Dynasty landscape painting, Background Story, 2012, (Fig. 5.1) was the first thing we saw as we entered the museum. We knew the contemporary art of Xu would not include a traditional ink painting like this one. Confused, we looked around, noticed debris laying near it and wondered why it was such a mess. Curiosity pulled us closer to the artwork where we saw ordinary materials like paper, hemp and plant material pressed up against the frosted glass with tape and other adhesives. See Fig. 5.2, Background Story (backside), 2012. Amused, we knew we were in the right place; deflection is a cornerstone of Xu’s work.

Xu Bing uses his Buddhist practice to solve complex problems that the subjective egoic mind cannot. His artwork is a resultant communication from the innate and conscious mind. Xu is a transdisciplinary artist focusing on transformation in the fields of language, history, sociology, psychology, and philosophy. Mediums include print making, calligraphy, sculpture, writing, videography, filmmaking, space art, and installation art. He lives in Beijing where he serves as the director of the Central Academy of Fine Arts and in New York where he is a Cornell A.D. White Professor-at-large.

Xu is a pioneering contemporary Chinese artist. He has exhibited internationally and has works in the most prestigious museums in the world and has taken part in the 45th, 51st, and 56th Venice Biennale. He received the MacArthur Foundation “genius” award, the 14th Fukuoka Asian Culture award for his “contribution of Asian culture” and the first World Arts Award in Wales. Columbia University gave him the title of Doctor of Humane Letters in 2014 and the United States awarded him the State Department’s Medal of Arts for his efforts to promote cultural understanding.

His work with calligraphy and printmaking, his experiences within two different Chinese cultures, and his adoption of the Buddhist philosophy was the glue that brought together his subsequent work, for example, Book from the Sky, 1988 (Fig. 5.3 and 5.4). [Note: In Buddhism, there is no written doctrine, like the Bible, the Torah, or Koran]. Information comes through meditation and is self-guided, as D. T. Suzuki taught, “Zen proposes its solution by directly appealing to facts of personal experience and not to book-knowledge. The nature of one’s own being where apparently rages the struggle between the finite and the infinite is to be grasped by a higher faculty than the intellect.” 1 Perhaps Xu’s most sacred art, Book from the Sky, shows no matter how much you look to the outside for knowledge, you will never find it. This installation acts as a koan—a method to trap our subjective ego and find enlightenment.

This work was first exhibited in the National Art Museum of China, showing 4,000 characters in four volumes of 604 pages. The critics considered it an important part of the 1985 Fine Arts New Wave: the birth of Chinese contemporary art that characterized the broad liberalization movement in the years since the Cultural Revolution. In this work, we see where the traditional materials, crafts, and techniques take a backseat to the concept of arbitrariness of language and a desire to subvert the audience’s linguistic and cognitive expectations. There is no one who can read or comprehend this calligraphy, including Xu Bing.

Xu’s comments about this work show his method for getting beyond the self-referential egoic mind and moving into the innate mind. As he describes,

My personal need to create the work was also related to a particular cultural condition and moment, prompted in the first place by my reaction against the post-Cultural Revolution ‘cultural fever’ I participated very actively in this trend: I was reading a lot and constantly engaged in discussions, but somehow, I was falling too deeply into it, getting lost in it. I was increasingly put off and disappointed by the game of books and culture, like a hungry man who had eaten too much too fast and was starting to feel sick. … I thought, ‘I need to make my own book to express my feelings toward books. … and every day when I worked on those ‘meaningless’ characters, it was like having a dialogue with nature. There was no intrusion of knowledge or of argument. My thinking, in turn, became clean and clear. This was not about creating a piece of art, but about entering the realm of meditation. 2

#

Xu Bing’s artwork always took me beyond my ego and allowed me to shift perspectives quickly. Through years of research, my personal truths grew and I could see Universal Truth in his work more quickly. His method of deflection guaranteed a sense of humor, which made the conceptual part of his work easier to understand.

Xu had an enormous influence on my work. Pulling together a gallery presentation entitled Sweet Tea Garden, as seen under the heading Installation Art. I wanted to show how I used Buddhism in my everyday life living in the Low Country. As I thought about the many ways I could do this, I remembered the landscape, Background Story, and was, once again, overtaken with amusement. Wanting to share this elation, I started building the case and gathered landscape material from the maritime forest near my home in the Low Country. Even though my “ink painting” landscape was not as perfect as his, I loved every minute of building it.

The book, Tao Te Ching, is the foundational text in all religions and philosophies. It discusses the unfathomable universe and the power that is given to an individual following the Tao (the way). Zen and its ideas trace back to this—the oldest book written in 400 BC by the sage, Laozi. While preparing for my thesis exhibit, Zen and the Art of the Journal (shown under the heading Installation Art). I studied, interpreted, and illustrated the eighty-one chapters. I made some of them into scrolls like Chapter One to represent my studies in grad school. This chapter talks about transition. My interpretation reads:

The Tao that can be told is not the Eternal Tao.

The name that can be named is not the Eternal Name.

Nothingness is the origin of heaven and earth.

Beingness is the mother of the Ten Thousand Things.

When you are free of desire,

You will understand the essence of your life.

When you identify with your desires,

You will observe the manifestations of your life.

Both contain the deeper secrets arising from the dark unknown,

The Doorway to the mysteries of Life.

Taking a lesson from many of Xu’s works as koans, I also used them in my conceptual work. See my work on this website under the heading Koans. The purpose of them is not to teach anything, but to allow the viewer to experience the state of consciousness beyond the ego. In a sense, the viewer steps into the artist’s realization. In Book of the Sky, the viewer realizes how “empty” the characters are and how easily he fooled himself into giving the carved “words” importance beforehand. Viewers question the dependability of writing and the limits of the cultural perspective as owned by the status quo. The art is paradoxical to the thinking mind and agitates the ego. It is used to provoke the ego out of its false sense of security—the fear of changing. In fact, the only thing we count as true is that all of life is impermanent and dynamic.

Figure 6.1, Val Britton, Intimate Immensity, 2013, San Jose Institute of Contemporary Art, San Jose, California

Figure 6.2, Val Britton, Voyage, 2015, San Francisco International Airport, San Francisco, California

Chapter Six

Finding Intimate Immensity

French philosopher Gaston Bachelard discussed how meditation (or daydreams) are tools to tap into the unconscious mind to find hidden truths and increase creativity. In his The Poetics of Space: The Classic Look at How We Experience Intimate Places, we find an entire chapter devoted to this subject.

One might say that immensity is a philosophical category of daydream. Daydreams undoubtedly feed on all kinds of sights, but through a sort of natural inclination, it contemplates grandeur. And this contemplation produces an attitude that is so special, an inner state that is so unlike any other, that the daydream transports the dreamer outside the immediate world to a world that bears the mark of infinity. Far from the immensities of sea and land, merely through memory, we can recapture, by means of meditation, the resonances of this contemplation of grandeur. 1

In analyzing images of immensity, we should realize within ourselves the pure being of pure imagination. It then becomes clear that works of art are the by- products of this existentialism of the imagining being. In this direction of daydreams of immensity, the real product is consciousness of enlargement. We feel that we have been promoted to the dignity of the admiring being.

This being the case, in this meditation, we are not ‘cast into the world’, since we open the world, as it were, by transcending the world seen as it is, or as it was, before we started dreaming. And even if we are aware of our own paltry selves- through the effects of harsh dialectics- we become aware of grandeur. We then return to the natural activity of our magnifying being.

Immensity is within ourselves. It is attached to a sort of expansion of being that life curbs and cautions arrests, but which starts again when we are alone. As soon as we become motionless, we are elsewhere; we are dreaming in a world that is immense. Indeed, immensity is the movement of motionless man. It is one of the dynamic characteristics of quiet daydreaming. 2

As Bachelard continues, “Grandeur does not come from the spectacle witnesses but from the unfathomable depths of vast thoughts.” 3 When the artist taps into the enormity of his meditation, or his unconscious mind, he gathers information that concentrates on the intensity of the human experience and allows us to know something which we did not know on a conscious level. By going deeper than the subconscious, past the beliefs, opinions, and judgements, we can discern truths.

Meditation, a program that focuses our attention inward, produces a state of deep relaxation or daydreaming. It develops areas of the brain associated with memory, compassion, and empathy—allowing us to relate to all humanity. The part of the brain associated with fear, stress, and anxiety shrinks as we become more comfortable being with ourselves. The physiological changes become permanent as the anxiety neurotransmitters decrease and the dopamine neurotransmitter increases. These subtle changes result in an overall feeling of health improvement and wellbeing.

We know meditation affects the brain by rewiring it, taking out our old unhelpful patterns and replacing them in the subconscious with helpful ones. These changes make us more creative, more aware, and more focused when not in a state of meditation. The more we meditate, the more advantages we realize. Common aspects across all creative fields are openness to inner journeys, the ability to extract order from chaos, and the willingness to take risks. The creative process draws on the use of both subconscious and conscious minds working together and recruiting different areas of the brain to form the team necessary to get the job done. Meditation makes us masters of our own mind.

#

I became curious about contemporary artists (both well-known and less so) whose works I felt showed these characteristics. I was also interested in how these artists defined their processes of creativity and how their inspiration came into play.

One such artist is Val Britton. She is a multidisciplinary conceptual artist working in collages, sculptures, installations, and glass murals. She works in an organic intuitive way to create artworks inspired by Bachelard’s the Poetics of Space like Intimate Immensity (Fig. 6.1). As Britton explains, “Collage, drawing, painting, and cutting paper have become my methods for navigating the blurry terrain of memory and imagination. I am interested in exploring the tension between chaos and imposed order, the concrete, and the imaginary, and the known and unknown”. 4

Britton studied printmaking abroad at the Edinburgh College of Art. She calls herself “a good draftsman” that did a lot of printmaking, lithography, and silkscreen. and fell in love with “accidents” and the element of wonder every time she pulled a print off the press. Britton received her BFA from the Rhode Island School of Design and her MFA from the California College of the Arts in 2006. Her works hang in the following collections: Facebook Corporate Headquarters, New York Public Library, New York Historical Society, Library of Congress, National September 11 Memorial and Museum, Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, The Cleveland Clinic Fine Arts Collection, the San Francisco International Airport, among others.

Commenting on her grad school days, Britton said that it was a time of accelerated growth. It allowed her time, space, focus, and challenges to push her work forward. By the time she graduated, she had tapped into the core of what was important to her. Britton knew what she wanted to say. She had developed a meditative process and some material interests and techniques that gave her confidence. She learned to trust herself and to listen to her voice amidst all the noise.

Educator, writer, and artist Scott Thorp interviewed Britton. He described her work as referencing cartography and asked, “Can you speak a little about your history with maps and how they serve as inspiration?” Britton responded,

I began working with maps in graduate school over a decade ago. While driving across the country from Brooklyn to San Francisco, where I was to begin school, I used an atlas to guide my way and to find state parks where I could camp over the two-week journey. This was in the era before GPS and smartphones were part of my life. In addition to being a practical tool, the atlas provided a language I adopted as a way to connect to my father’s story as a long-haul truck driver and mechanic, to make sense of his loss when I was younger, as well as a way to think about my own changing geography and sense of place. I began sketching out sections of his interstate routes, tracing them and using the map networks as scaffolding on which to build larger, more expansive drawings where I could insert my hand and identity… This journey became about time as well as space, a meditative experience of charting time spent with the work and developing a visual vocabulary… I am applying the map language to my internal, invented landscapes. I am suggesting multiple interpretations and ways of navigating these systems and being guided by each move that I make along the way: creating a problem, digging in, and then trying to work my way out. Over time, my works have strayed from actual places to become more abstract and almost entirely invented. 5

To live a curiosity-driven life, creatives must find their own personal inspiration. As in Britton’s description, cartography was at that point of interest for her. Maps are open and connectable in every direction, much like our personal journey. The parts of the maps are highly malleable, allowing them to be torn, detached, reversed, and capable of both dynamic and subtle changes. We can conceive them as a work of art or as meditation. In our childhood, fearless enthusiasm ignites the journey of discovery. As we get older, most of us trade curiosity and wonder for certainty and security. Paradoxically, it is only as an adult that our brains have developed enough to process creativity and turn puzzles into plans and ideas. Britton achieves new depths of knowledge by reverting to her subconscious mind to explore, question, and travel to the unknown. Her experiences, combined with curiosity, lead to revolutionary creativity.

Neuroscientist David Eagleman explains,

The human brain owes its creative success to the fact that inputs are constantly being smashed together with other inputs. So, sights, and smells, and sounds, conversations, and ideas—these are constantly reconfigured in the brain. Every second of your life, inputs from your world are being walked on and combined with what is already there. Creativity is not about one region of the brain. Instead, it emerges from interplay of billions of neurons sending trillions of electrical impulses—sights, sounds are mixing with memories, thoughts, emotions—new and old. So, every experience you have is raw material for your brain to create with and all these inputs get fashioned into new ideas. 6

In 2015, Britton completed an installation for the San Francisco International Airport. Voyage (Fig. 6.2) is composed of 15 laminated glass panels measuring nearly 9.5 feet tall and 55 feet wide. Franz Mayer & Company fabricated the panoramic piece in Munich, Germany. Britton researched the history of the airport, the land it sits on, weather patterns, and passenger statistics. She used plans of the airport, a map of the bay, wind patterns, flight routes and topography to generate imagery. Britton described her work:

The piece is based on a collage made in my studio, made of paper, ink, and graphite. Working collaboratively with the artisans at Mayer, we translated the collage into glass panels. Some elements have been stenciled and hand painted using melting colors, which are fired in the kiln akin to ceramic glazes. These painted areas have an inky/watercolor quality. Other areas have been etched and filled with pigment. One layer is drawn with graphite, and the back is stenciled and painted with opaque colors. 7

Figure 7.1, Teresita Fernández, Blind Blue Landscape, 2010, Benesse House Hotel, Naoshima, Japan

Figure 7.2, Teresita Fernández, Dark Earth, 2021, Maria and Alberto de la Cruz Art Gallery at Georgetown University, Washington, DC

Chapter Seven

Beyond The Observable

Innovator Teresita Fernández makes work that transcends language. She sees beyond the boundaries of her mediums and her materials to create art so imaginative it changes the viewer’s perspective. Her mediums include sculpture, public art, relief panels, wall drawings, and installation art. She invites her audience to take part using their mental faculties and all their senses. Fernández describes her installation art this way: “The sense of intimacy is, I think, what’s transportive. It’s an idea linked to phenomenology that’s about, for lack of a better word, a kind of significant daydreaming. It’s about projecting yourself into something and moving through a space without necessarily physically moving through it. It’s a different way of inhabiting a place.” 1

Fernández and her art captured me on a personal level. From observing her spiritual work, I felt she, too, was on a personal pilgrimage. The more I knew her work, the more I knew her and the more I understood human nature. She made me more aware of the likenesses we all share, as influenced by her grandmother, who taught her “cada persona es un mundo”.

As Fernández said, “One of the most interesting things about being an artist is that my work is based on this very strange way of linking and making connections between things that normally would have nothing to do with one another.” 2 This type of thinking is touted as the most creative thinking skill we can master. It is an intuitive way of seeing and a knowingness born of the unconscious mind. Fernández combines research and philosophy, which allows her to absorb the meaning and understand how the information can come together to produce specific effects on the audience. She sees her landscape work as a mirror of an all-encompassing immensity, reflecting on the audience their greatness. Fernández explains this type of transmutation this way.

In Bantu-Kongo cosmology, which informs so much of Afro-Cuban Socratic religions, there’s a symbol of Ikenga (strength of movement). Which is the four cardinal directions, kind of like an alchemical process… north, east, south, west, and then the last, the last direction, the fifth direction, is actually inward. And it’s the hardest one to understand. It’s the hardest one to enter, an idea that, when you enter that final direction, what you get is the outside again. You get this immense cosmic thing that is you. 3

Fernández takes us far beyond the observable into her journey seeking Truths. Creating art can be a companion to take us from the intimate to the monumental. It is the ultimate vulnerability—we must know, trust, and love ourselves to stay with the uncomfortable for a long period. It is formidable to realize how empty an artist must be to pick out subtle Truths and to give shape to them. Jung linked this collective unconsciousness to Freud’s archaic remnants–mental forms “whose presence cannot be explained by anything in the individual’s own life, and which seem to be aboriginal, innate, and inherited shapes of the human mind.” 4 Artists consider the concept of everything that has come before in the collective unconscious, her experiences, and the interdependency of history and research. Moments of lucidity are short-lived and indelible—they are the Truth. The irony of being an artist is you cannot lie to yourself. Truths rely on intuition and must unfold on their own.

As in Fernández’s case, inspiration comes before creation and is used to ignite the idea into form. As she explains,

The art is when I put together different bits of cultural and historical artifacts and information. Suddenly, it’s a new project—then I figure out how it’s going to look. This is why I always say the work is completely conceptual. It takes a lot of research to get there. I’ll read ten books that have nothing to do with each other, just looking for that little tidbit. Research is a very blind act of searching and searching. It’s like going down the rabbit hole. It takes you one place and then takes you somewhere else. It’s not theoretical research. I travel, I read literature; I look, I watch films. I’m interested in the historical and cultural context of places and materials. I look at materials not only for their physical qualities—which are important—but also for the conceptual framework they represent. 5

Fernández views all her landscape works as figurative—simultaneously including the audience in it. Her landscapes are not replications, but conceptual anthropological understanding of geography’s psychic, historical and cosmic place. Her practice unravels the intimacies between nature and human beings.

In 2010, the organization of the First Setouchi Triennale on Naoshima, Japan’s Art Island, commissioned Fernández to produce a work. She composed the poetic and beautiful Blind Blue Landscape made of nearly 30,000 hexahedrons of mirror. The tiny little lamps change depending on the time of day from sunrise to sunset. They mirror everything happening atmospherically in the park and the shore nearby, each becoming a miniature landscape. Curious observers recognize the innate truth that we are the figurative version of this poetic nature—of all nature. We actively create landscapes when we become part of it. Blind Blue Landscape is like an enormous mirror of the Naoshima place itself.

In her series, Dark Earth, we find her use of chromed metal and charcoal to suggest buried layers and violent histories of place. Her panoramic views not only designate the physicality of the terrain, but the history of man’s use and abuse of it. Because of Fernández’s use of the figurative in her landscapes, we look for the figure in this series, too. The chromed metal allows us to see our reflected selves. The thousands of slivers of charcoal, the burned earth, demands we see our destructive side in the earth’s demise.

As Fernández said, “Looking at the landscape is never passive; you are in the landscape, but the landscape, and everything that has happened there, is in turn also inside you.” 6 Dark Earth continues to challenge our ordinary notions of landscapes. In this series, Fernández unearths the historical violence embedded in our ideas of the earth. Complacency stays with us as we maintain a warped sense of time. This status quo attitude helps us maintain our beliefs that our past and future do not affect us. But our bodies are archival repositories of our ancestors, of everything that came before us, of our collective unconsciousness. We cannot stand by and allow further destruction to this place and assume no responsibility. As we study the carved slivers of charcoal in Dark Earth, we realize we are a part of our planet’s evolution. We become enlightened when we realize the illusionary belief that what we say and do only affects today. The world’s history is our history and what we think and do drives evolution. This series speaks of the desire to become something better—to replace greed with sustainability of natural resources, to replace colonization and annihilation with sustainable construction for future civilizations.

Fernández’s artwork uses mythopoeic concepts to show us to ourselves; to better understand who we are. Our world is not one of impersonal laws, but one of personal intentions. Contemporary man sees this world as an “It”, indigenous man sees the world as “Thou”. Her works inspire and motivate us, rather than replicate outdated models of “It”.