THE BOOK – Part II

Chapter Eight

Educating the Creative

As my second semester began, I joined the painting department as a grad assistant. My assignments comprised shadowing the professors, proctoring tests, tutoring specific students, setting up classroom assignments, researching and managing toxic waste from oil painting materials, and doing all the other things the teachers did not want to do. As I contemplated becoming a professor, I watched to see how creativity played a part in teaching art.

The painting professors did not hold an education degree or attend any education courses. One course in pedagogy is the only requirement, which teaches the mechanics of running a class. Lessons include resources, learning assessments, behavior management strategies, giving demonstrations, and classroom seating plans. From my experience, I knew that education courses helped prospective teachers learn human behavior and how to maximize the learning possibilities of individual students. Here, the emphasis laid solely on the teaching side of the equation, setting up an explicit system.

Coming from the opposite position—that of having the courses, but not the experience—I earned my first degree, a BA in Education. As part of a group of graduating seniors, they sent me out to practice teaching in the Atlanta City School System in my last quarter.

They assigned me a small sixth-grade class, which included twelve minority males living in poverty. They labeled all of them as functionally illiterate and placed them in the middle of an open classroom. The school system divided these large rooms into different pods, all teaching different subjects at the same time. I knew I could not concentrate under those conditions, and neither could they. The first thing I did was move our class outside where a section of the playing field remained our classroom on clear days.

My students were sixteen years old and scheduled to be expelled from the school system in three months. Instead of teaching the assigned subject, I set up an implicit teaching system. Embracing a guide-on-the-side teaching role, empowering the students to take ownership of their learning from the very beginning. Concentrating on each student and what they needed to survive at sixteen on the streets of Atlanta, I went to various fast-food chains, grocery stores, and other businesses to pick up job applications. We used these forms as lessons, and we discussed interview questions and procedures. They brought comic books, sports magazines, and other materials to read in class, as I knew they were more likely to read books they wanted to read. I found out that they could all read and write but did not test well on standardized achievement tests—averaging their reading skills at the fourth-grade level.

By setting up this creative environment, I stimulated their divergent thinking and used the class as a community of supporters. We all learned through trial and error using imagination and critical thinking to solve problems like application and interview questions. This learning environment helped the students practice and develop their own answers with confidence.

During our last month together, I found out that one student had an R&B band. I arranged for his crew to perform for the school on our last day of classes. My small group of students were proud that they were the stars that day. The band was fantastic and brought the house down. Never had I seen such ecstatic kids. I was thankful for the chance to know them. I felt secure knowing they had a clear sense of their own ability, a strong support system with each other, and tremendous coping skills. Together, they overcame the stigma of being cast illiterate. But we have not designed our systems to support kids like these. The Department of Justice states, “The link between academic failure and delinquency, violence, and crime is welded to reading failure. Over 70% of inmates in America’s prisons cannot read above a fourth-grade level.” 1

After that experience, I never wanted to teach. I just could not condone the broken systems I had witnessed firsthand. I know these kids had the ability to read and solve problems. Perhaps by changing the teacher/learner experience, they could find success. And by changing my environment, perhaps I too could find success and happiness.

#

As newborns, we begin our lives as part of a collective consciousness. We develop curiosity and free will. During the first seven years of life, our brain waves are slow, but they have all the instincts necessary to survive and learn. As infants, we are very susceptible to our first teachers—our caretakers. Meanwhile, 90% of the time, these guardians are unaware of this dynamic. Our interdependent conscious minds emulate what the caregivers are doing, not what they are saying. These observable bits and pieces become part of our permanent default programming, the conscious with its central development of the ego. As ego develops, our connection with instinct (or spiritual guidance) becomes less prominent and a more self-centered ego develops. Major parts of our whole psyche become relegated to the subconscious portion of our minds. Over time, this information moves to the unconscious. Families and peer pressure continue to condition our egos and so we remain unconscious of our authenticity—the totality of the whole psyche—which remains hidden for at least the first half of life.

By the time we enter school, we develop skills for good emotional health and strong social skills. Discoveries of self-awareness begin as we continue to grow. Emotional states and their subsequent relation to thoughts and behaviors come into play as our self-centered egos and consciousness continue to develop. The school system insists upon emotional regulation for control and students easily comply—they neither like change, nor do they like being challenged. The status quo is rigid and being part of it blinds us to truth. Only through change comes progress.

Children are born with the natural ability to empathize. We should encourage them to continue in this capacity to care for others, even though the ego holds itself out as separated from the rest of humanity. Their relationships are paramount in healthy communities and in the future of this planet. Through the dynamics of school socialization, children either learn to be stewards of this earth or use their ego as a mental organ for defensiveness. “Giving to get” is an inescapable law of the ego. Because it lives by comparisons, equality and charity are difficult to grasp.

The most important creative growth comes from the child’s curiosity—his processes of asking questions, creating scenarios, and entering discussions. This general exploratory approach is an extraordinary way to discover that everything works together and feeds the need to be lifelong learners. The child discovers relationships through stories, patterns, and functionality. Inside these relationships, ethics, and aesthetic meanings surface. Children will surprise us with their discoveries if left to their own devices. It is the adults’ job to provide the intellectual and full range context for these processes to occur.

We cannot separate building the physical and spiritual from cognitive development. Children learn through language beyond words, through the physicality of action, through sensations, through doing. Art gives children another way to communicate with each other beyond language—through hands-on experience. Expressing through art is a natural aptitude present in all children.

After early childhood, the subconscious mind comprises a large bank of accessible information, a reservoir of emotions, thoughts, beliefs, and memories from the past––outside of conscious awareness. Where we put our focus determines our outcome; what we think, we create. Even as we harbor untruths about ourselves, we will find “proof” for it. As Henry Ford said, “Whether you think you can, or think you can’t… you’re right.” 2

Hopefully, by the time children enter first grade, their imagination and divergent thinking has blossomed and is so ingrained in their personality that the school system cannot destroy their originality. But research shows that student creativity at the kindergarten to senior high school level has been in significant decline for the last few decades. Based on scores from the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking, Kyung Hee Kim at the College of William and Mary reveals, “That children have become less emotionally expressive, less energetic, less talkative, and verbally expressive, less humorous, less imaginative, less unconventional, less lively and passionate, less perceptive, less apt to connect seemingly irrelevant things, less synthesizing, and less likely to see things from a different angle.” 3

During this same period, there has been a steady decline in the number of startups and a failure in America’s education model which “fails to promote the kind of creativity, risk-taking, and problem-solving skills necessary for entrepreneurship, and for a world and labor market that is in the midst of profound transformation.” 4

Because schools retool their students to become obedient workers, they are told how to behave and react. Instead of divergent thinking, we teach them that there is only one right answer. Stephen T. Asma, philosophy professor at Columbia College Chicago, acknowledges, “We need a new kind of approach to learning that shifts imagination from the periphery to the foundation of all knowledge.” Asma continues, “It is time to initiate Imagination Studies at every level of education, primary school through university. Studying the imagination—its creations, its processes, and its underlying cognitive structures—is the most exciting and accurate way to heal the terminal divide between the sciences and humanities. But more importantly, Imagination Studies, or Imaginology, also promises to reunite the body and the mind, reintegrate emotion and reason, and tesselate facts and values.” 5

Educator and author Sir Ken Robinson discusses the need to reevaluate education. He calls on us to “reconstitute our conception of the richness of human capacity” as today’s “creativity is as important as literacy” and should be treated with the same status. 6 In his TED Talk, Robinson searched for a solution,

Life is not linear, it is organic. We create our lives symbiotically as we explore our talents in relationship to circumstances; they help create for us. But we have become obsessed with this linear narrative. Human communities depend upon a diversity of talent, not a singular conception of ability. And at the heart of the challenge is to reconstitute our sense of ability and of intelligence. This linearity thing is a problem. The other problem is conformity. We have built our education systems on the model of fast food. It’s impoverishing our spirit and our energies as much as fast food is depleting our physical bodies. We have to let go of what is essentially an industrial model of education, a manufacturing model, which is based on linearity and conformity and batching people.

We have to move to a model that is based more on principles of agriculture. We have to recognize that human flourishing is not a mechanical process; it’s an organic process. You cannot predict the outcome of human development. All you can do, like a farmer, is create the conditions under which they will begin to flourish. So, when we look at reforming education and transforming it, it isn’t like cloning a system. It’s about customizing to your circumstances and personalizing education to the people you’re actually teaching. And doing that, I think, is the answer to the future, because it’s not scaling a new solution; it’s about creating a movement in education in which people develop their own solutions, but with external support based on a personalized curriculum. 7

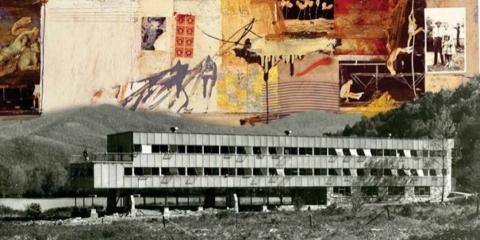

Figure 9.1, Black Mountain College, 1933-1957, Black Mountain, North Carolina

Chapter Nine

The Agony of the Artist

It was interesting, to me, to witness where in-coming college art students were in their development toward creative thinking. After all, these were the art students who survived the school system and supposedly were in a place where their inventiveness could thrive.

To give you a typical example of a BFA painting class, we set tables up in the middle of the room to house clustered objects with easels surrounding them so that each student could choose a section, or a tableau, to replicate. The instructor then told them to apply color in order to produce a mood that would enhance their still life. This technique is called visual development, where color, design, and composition are techniques taught to enhance one’s craft. Both the replication and the additional color are techniques taught to develop skills in painting. This kind of environment does not encourage creative thinking. The students stayed in their comfort zones and turned-out artwork that was easily graded—it either looked like the tableau, or not—and color enhanced the mood, or not. The lesson taught nothing about art—about inward significance.

In another painting class, the professor instructed the students to dress up and get photographed to portray “who they were”. Then paint their self-portrait copying the photograph. For example, one student encircled her neck in an oversized heavy chain, conveying her drug addiction. Once again, the teacher failed to create a situation that encouraged creativity. All I witnessed was a replication of her ego—her self-identified appearance, not inward essence.

I could not understand why any of them even came to class. Why pay these high tuition fees for something they could have done at home without a teacher? If an artist desires to copy images, practice is the only requirement. The tuition money would have been better spent investing in a studio or joining an artist co-op.

An artist must know who he is and why he is an artist—that information must motivate and inform the work. Cheryl Arutt, PsyD, a licensed clinical psychologist specializing in creative artist issues, understands that “If you are an artist, you are your instrument. The greater access you maintain to yourself, the richer and broader your array of creative tools.” 1 More than any other career, being an artist means always starting from nothing. It is almost entirely inquiry based and self-regulated. Spending time alone allows the artist time to embody non-discriminatory wisdom vis-à-vis the meditational and/or art experience. This would make it easier for him to find out his strengths and weaknesses. And allow him to identify his creative obsessions, which become so specific that we could only recognize his work as his own.

Art requires a willingness to stay open. No matter how many successes there are, there will be failures. Every project starts blind as a profound mystery, and the need to lean in to get a closer look at what we are creating is always there. We must pursue art from both the inside and outside at the same time. We realize the inside is driving the outside when we take a closer look. As artists, we will be the only ones to recognize and enjoy that internal success. Satori is a Zen Buddhist term for this type of awakening. The literal translation is seeing into one’s true nature.

An environment that fosters creativity should include the time and opportunity to practice creative thinking, beginning with broad ideas instead of specific ones, and reward divergent views and innovative outcomes. We should encourage the motivation for prudent risks, allow for mistakes, and discuss other viewpoints. Allow the student to question their beliefs and assumptions by allowing them to consider their interests and problems. This practice enables students to find their voice in all content areas when they use divergent thinking to generate many ideas and then use convergent reasoning to provide the best result. This technique is useful in decision making and is an indicator of notable achievement.

We know that artists, entrepreneurs, and innovators fail many times before success. Creatives do not learn from a teacher’s dictates, but from their own experiences. Frustration, pain, and confusion are part of this process. The value of agony or difficulty cannot be over-emphasized; It will become part of who he is and possibly why he is an artist. In Japan, there is a reverence for the art of mending broken pottery named kintsugi. It means to repair with seams of gold. The most common history I had found for this practice dates to the 15th century, when a shogun needed a broken bowl repaired. Those repaired bowls became more prized than the original pottery. There were a few artisans that were proficient in this technique. These bowls, with their rivers of gold, became distinctive because they resembled nothing but themselves. These times of struggle, these searches for answers, these starts and stops, these breaks and repairs eventually steer the artist in the right direction.

#

I worked as a grad assistant for this one semester only. I lost my ambition to be a professor and found myself disappointed in higher education. This time, the travesty seemed worse. Watching the talents of creative people squandered on replication was unbearable. We teach art students the technical rules and then tell them to throw the rules away and develop their voice. I never witnessed that transference taking place; I saw the same outdated linear thinking being taught ego to ego decade after decade. Even today, academicians and non-artists define an artist as someone who can draw by replicating what they see. Most people do not know the power of art as transformative, not even the professors that teach it.

It is possible for artists to never produce a piece of Fine Art. But according to the Artistic Archetype, this is an unlikely probability based on the way art manifests itself in the artist’s psyche. All of us can produce art because we are all creators. Most create from the self-centered ego, which has no resemblance to the Archetype of Art itself—an autonomous expression of reality. Fine Art is not a copy of something else. It comes by the nature of the artist as creator and manifests in the same way the artist views the world without a self-centered ego. Otherwise, any creation will come from the hand as opposed to the soul and result in expressions of reality that are deluding and anamorphic.

Each of us has our own unique profile of cognitive strengths and weaknesses, but none of us must live with limitations. In a creative environment, we can harness the brain’s changeable characteristics and expand it to think like a polymath. An open environment encourages us to learn new things. We put together new concepts and understand their connection. This is how we change the plasticity of our brains, changing the physical brain itself. By creating a place of possibilities, we develop new learning processes. A place where learners dare to dream and realize those dreams. The arts wake us up, sharpen our senses, and take us away from our sensory realities to encounter the very nature of our existence in the fullest sense.

Contemporary artists, those other than commercial artists and academicians, reflect that they know themselves through their work. E. E. Cummings defined this type of artist as “The Agony of the Artist (with a capital A)”. The article originally appeared in Vanity Fair in 1927 and was one of the forty-nine essays in the now unavailable book entitled A Miscellany Revised. As Cummings defines it,

It is Art because it is alive. It proves that, if you and I are to create at all, we must create with today and let all the art schools and Medicis in the universe go hang themselves with yesterday’s rope. It teaches us that we have made a profound error in trying to learn Art, since whatever Art stands for is whatever cannot be learned. Indeed, the Artist is no other than he who unlearns what he has learned in order to know himself; and the agony of the Artist, far from being the result of the world’s failure to discover and appreciate him, arises from his own personal struggle to discover, to appreciate and finally to express himself. 2

As we learn to value the gift of creativity, we learn to value the responsibility that goes with it. We can no longer use our ignorance as an excuse to be irresponsible and uncaring. Our scars in life guide us in new and more meaningful ways—to create a thing personal to us, enabling us to create a new thing that has never existed before. Often, these revelations need an explanation from the unconscious, which may take time to understand. It is a riddle that solves itself. By putting a question on the back burner, we allow for incubation and time for divination to kick in.

Enlightenment occurs unexpectantly, way beyond logical comprehension. Could it be that both Buddhist practitioners and conceptual artists find this insight into their self-guided approach to life itself? The relationship between meditation and the creative process runs parallel. They both live in a space of open-mindedness (free of prejudices), satisfying curiosity and risk taking. And they both allow for direction from the surfacing of humbling inner knowledge through intuition. Embracing discomfort is essential. Flow, mindfulness, meditation, and creativity require complete concentration in the now. We are all built for peak performance—flow is universal in humans as it is in nature. Mindfulness provides discipline while curiosity provides the motivation to get us in the receptive position. Learning allows us to remain curious and pushes our research further. The act of creativity steers us, and flow amplifies the results beyond expectation.

As I realized my teachers were not able to get beyond their own self-centered egos, I simply produced the work required. But I continued to study aesthetic polymaths who showed multidisciplinary talents. Their work guided me to take time to respond to my internal inspirations, rather than external expectations of others. As excellent communicators, I realized these self-actualized artists were gifts to society. I learned that there are as many roads to discovery as people on the face of the earth. They all serve as guides to show us the powerful creative forces inside each of us. Development of self-direction to study what we cannot resist and fostering compassion leads to a harmonious semi-effortless life. When we become our own self-educated oracle, we learn as Zen shows that which we are looking for is that which is looking.

#

My art school experiences were unfortunate, for this place certainly was no Black Mountain College. From 1933 to 1957, the College asked their students to be awake on the threshold of perception. Whether in art, at work, or community life, they stood on the edge of the known and the unknown. It was a safe place for risk-taking and collaboration in every aspect of their lives where the artists learned from the mathematicians and vice versa; the scientists wrote poetry as the poets performed scientific experiments. The faculty (who owned the college) taught transdisciplinary studies. Their goal was not to teach students disciplines or techniques to study, but to form thinking individuals who shaped their democracy and perceived the world with ethical clarity. Showering the students with respect gave meaning and consequence to everything they did.

By not accepting the traditional university type of thinking, they rid themselves of unimaginative specialized linear convergent thinking. The founder, John Andrew Rice, insisted upon “the freedom to learn in one’s own way and according to one’s own timetable”.3 They had free access to everything. There were no grading systems, no tests, and no degrees. The students completed their schooling when they left campus. The students and faculty worked, socialized, and lived together. They established a sustainable lifestyle by growing their own food, constructing their buildings, and working in the kitchen. The founder created a John Dewey type educational system that worked to produce self-realized individuals that were active and outspoken members of society. Both Rice and Dewey established this educational system to not relegate creativity and art to the sidelines, but rather made them the basis of all education.

The illustrious advisory board included Albert Einstein, John Dewey, Walter Gropius, Carl Jung, Max Lerner, and Wallace Locke, among others. World renown teachers included artists Josef and Anni Albers, architect Buckminster Fuller, critic Clement Greenberg, writer Paul Goodman, composer Stefan Wolpe, poet Robert Duncan, poet Hilda Morley, ceramist Marguerite Wilden Hain, potter Shoji Hamada, and filmmaker Arthur Penn, amongst others. Teachers often exchanged places with students, as it was a rare coming together of kindred spirits for interaction and experimentation—a lively, imaginative exchange of ideas.

And by the way, Black Mountain College gave the field of art some of their greatest thinkers—Robert Rauschenberg, Susan Weil, Jacob Lawrence, Cy Twombly, Robert Motherwell, David Tudor, Merce Cunningham, John Cage, Willem and Ellen de Kooning, Franz Kline, Robert De Niro, Sr, Robert Creeley, Dorothea Rockburne, Ruth Asawa, Hazel Larson Archer, and Charles Olson among others. The College was also the birthplace of performance art—originally known as the Happenings.

Nine decades after the College’s inception, people are still talking about it and crediting it with the biggest jumps in art history and with its creation of interdisciplinary work. Using creative thinkings as the backbone of everything, artists retooled themselves to think and work as unlimited polymaths. This unaccredited tiny college in the middle of nowhere has been the subject of ten full-sized history books, several poetry collections, and a continual topic of museum lectures across the world. Together, the faculty and students formed a community that amounted to the sum of its parts. And by doing so, generated an institution that gave rise to the utopian spirit and vision of the contemporary art world.

Recruited from the Bauhaus, both architect Walter Gropius and artist Joseph Albers brought their avant-garde and international style to the College. Their school had been closed by the Nazis under the guise of communist intellectualism. Both learned to speak English while teaching at the College—making this one of the most enduring aspects witnessed in this matrix of influence between faculty, board, and artists. “In short, our art instruction attempts first to teach the student to see in the widest sense,” Albers wrote in June 1934, “to open his eyes to the phenomena about him and, most important of all, to open to his own living, being, and doing.” 4

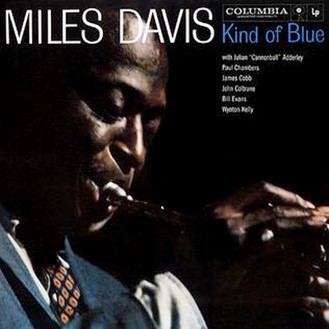

Figure 10.1, Miles Davis, Kind of Blue original album cover, 1959

Chapter Ten

Improv and Levitation

In pages from artist Theaster Gates Notebooks, 2016, Gates defines his future of art as different from what art is today.

When I build my school, I’m going to teach people that whatever is taught at the MFA level is akin to elementary school. In elementary school, students will learn replica, mise-en-scene, and representation. In middle school, they will learn about reflexivity, reproducibility, reaction, and reflection. In high school, students will learn to see the invisible, will learn physics and religion. As undergraduates, my future pupils will learn transgression, systems of power, how to be a system of power, and how to harness systems of power. They will learn how to mine for gold, dig for diamonds. They learn how to fish. In graduate school, students will learn how to levitate. Until we’re willing to think about the complexities, until we’re willing to think about the human capacity to understand complex symbols and thought forms and the invisible, we will think that murals alone can solve social problems. I would never make a mural to solve a social problem. It takes money to solve social problems; it takes hard conversations and political power—artists should also sculpt those things. 1

Times have never been better to learn how to “levitate” to become supernatural—to overcome the gravity of the status quo. Our world is complex and the need to understand complicated issues is paramount to our very survival. So, the question becomes, what do you want to cultivate? To develop a transcendent state, we must reach an uncommon place. Give when people live in poverty, show courage when people live in fear, and show compassion when people suffer. Doing things that are kind becomes supernatural. Past excuses take us back into complacency and keep us limited. Because Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. lived his ideas and manifested them simultaneously, we remember him as superhuman. Happiness is when what you think, say, and do is all in harmony. As King wrote in his sermon, “Three Dimensions of a Complete Life”: “Every man must decide whether he will walk in the light of creative altruism or the darkness of destructive selfishness. This is the judgment. Life’s most persistent and urgent question is ‘what are you doing for others?’” 2 A supernatural world happens when everyone gets beyond their personal limited thinking and learns how to think as a democracy to solve critical problems.

While working in my studio one night, I listened to the album Kind of Blue and remembered how Miles Davis always disarmed me and made me want to feel the way he sounded. Davis found his signature while playing with Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie in New York jazz clubs as a teenager. His sound reflected who he was—clear, even, vulnerable, and poetic—he became a master communicator. His life was challenging, but his curiosity kept him from standing still and playing it safe. To get beyond the status quo, he embraced change. Miles Davis continued to develop personally and redefine jazz his whole life.

While Davis was in Paris for a gig, a French filmmaker asked him to write the soundtrack for his new movie. They gave Davis a private screening of the film. “He apparently worked out some sparse harmonic sketches in his hotel room, and this was the only material he brought with him to the recording session. No themes, no parts, no lead sheets.” 3 He improvised the entire soundtrack with local musicians as he watched the movie again for its final recording. After recording this, Davis wondered what it would be like to make a record album using all improvisation; thus, no music was used to record Kind of Blue. Davis asked his sextet to think deeper about the sound they could create, and it changed jazz forever. I regard this album as the greatest jazz album ever recorded and it was one of the few that went mainstream. This release allowed us to witness spontaneity in a collaborative form as democracy entered the equation. To produce ingenious creativity, this incendiary sound, the musicians had to set their ego aside, stay in the present moment and shift into the flow state together. As Dr. Dispenza explains,

In order for us to truly change, we have to get beyond ourselves, and that is one of the arts of transformation. From the moment we are living in the moment, we cannot be running a program. All possibilities in the quantum field exist in the external now. When we can take our minds off of everything and live in the moment, we become pure consciousness. That is the moment we are no longer playing by the laws of Newtonian physics; we are no longer invested in the three- dimensional reality. Where we place our attention is where we place our energy. That place where we become nobody, no one, nothing, nowhere, no time is the moment we get beyond ourselves. It is that act of being in the present that allows us to see the possibilities that we could never see were we to stay in the place where we are stuck in our own programs and personalities. 4

In the liner notes of Kind of Blue, pianist Bill Evans describes their first encounter with democratic improvisation.

There is a Japanese visual art in which the artist is forced to be spontaneous. He must paint on a thin, stretched parchment with a special brush and black water paint in such a way that an unnatural or interrupted stroke will destroy the line or break through the parchment. Erasures or changes are impossible. These artists must practice a particular discipline, that of allowing the idea to express itself in communication with their hands in such a direct way that deliberation cannot interfere.

The resulting pictures lack the complex composition and textures of ordinary painting, but it is said that those who see will find something captured that escapes explanation. This conviction that directs deed is the most meaningful reflection I believe, has prompted the evolution of the extremely severe and unique disciplines of the jazz or improvising musician.

Group improvisation is a further challenge. Aside from the weighty technical problem of collective coherent thinking, there is the very human, even social need for sympathy from all members to bend for the common result. This most difficult problem, I think, is beautifully met and solved on this recording.

As the painter needs his framework of parchment, the improvising musical group needs its framework of time. Miles Davis presents here frameworks which are exquisite in their simplicity and yet contain all that is necessary to stimulate performance with a sure reference to the primary conception.

Miles conceived these settings only hours before the recording dates and arrived with sketches which showed to the group what was to be played. Therefore, you will hear something close to pure spontaneity in these performances. The group had never played these pieces prior to the recordings, and I think without exception, the first complete performance of each was a take. 5

This idea of democratic improvisation struck me as an example of a supernatural world, a group form of flow, or “levitation”. Jazz was born out of a fusion of blues and ragtime and has remained a fusion of ideas today, making it one of the most creative of musical genres. Just as Miles Davis handed Herbie Hancock an electronic piano and asked him to learn the instrument and form a complete rhythm section with it, Hancock took that seed and created supernatural democracy into musical multiplicities to describe multiple sources, multiple leveled music for the next decades.

Hancock’s curiosity has added funk to jazz, pop to jazz, disco to jazz, and through his 1983 Grammy for Rockit, introduced jazz with scratching, break dancing, and hip hop—taking hip hop from an underground stage to an international one. Hancock’s blank canvas carried exciting baggage. The various musicians on the album were recorded at multiple studios and at different times.

Hancock was a child prodigy, playing classical music at age eleven, played with Miles Davis and Blue Note Records at twenty-three. He found Buddhism ten years later when he began and still practices his Buddhist affirmation of the non-unity of self (Mushin) to this day. Hancock starts encounters all over the world; he cultivates creative contacts. These acts of conjunctures articulate relational humanity rather than bang up against ideas of unassailable conflicts or point out otherness. These collaborative projects also denote an orientation towards self-transformation, renewal, and vulnerability. A shift in Hancock’s self-perception started this form of cultural diplomacy and is pivotal to the discipline of improv. Hancock emphasizes we are all our most powerful when we create the future in real-time.

His forty-fifth album Possibilities featured a variety of guest musicians, from Christina Aguilera to Paul Simon to Carlos Santana to Annie Lennox to Sting to Wayne Shorter and more. Hancock produced a film by the same name depicting the collaborating artists in their discussions and performances. He was exploring the possibilities in himself, influenced by other people, the environment, and the times. Collaboration is an insightful journey into the spirit of possibilities.

Hancock talks about the night he discovered Buddhism. It was 1972, and his total focus was on playing music, and he considered himself on point. Buster Williams opened the first tune of the set and brought an energy that woke up everyone. The musicians tapped into his vibrations and played with a new intensity—they were on fire. After the gig, the audience rushed to the stage in tears, saying they had never experienced jazz like that before. Hancock cornered Williams to ask what had happened. The bassist said that he had been practicing Buddhism for only three months, which changed his life. He described his practice as allowing him to be aware at all times.

Creativity is difficult to explain. As Hancock says, “It transcends the brain or verbal descriptions. That’s why doing interviews, making speeches, or giving a lecture is a challenge because it requires words to describe an internal process that goes beyond what the brain can easily translate, and it’s just that process that gives the art of creativity its magic. It’s a zone within the greater self and a valuable place to inhabit.” 6

Lack of practice is the only way inspiration can be blocked. If we devote too little time to exploring options through practice, there will be nothing to pull from when it is time to enter the flow. Achieving a calm mind and body during any performance in life comes from a similar place; learned from the practices of meditation or mindfulness to pay attention to breathing. As we bring our attention to the breath, we realize the moment; we notice we are living in the now. This level of mindfulness, of course, is difficult. The mind looks for stimuli, awake and asleep. Through training your mind to be still for a few minutes each day, the change occurs, and the mind quiets. By going through these steps each day, you learn to observe your ego’s thoughts without judgement and let them go. This release allows room for spontaneity.

Hancock says, “A broader perspective of these characteristics reveals no essential difference between artists of culture and everyone else. A person who can live with imagination, hard work, innovation integrity, wisdom, and passion (despite difficult circumstances) can be a profound contributor to creating the harmonic human orchestra of life.” 7

Both Buddhism and Jazz rose from the fires of suffering, introspection, and compassion. Both live in the flow. Anyone absorbed in a task can lose the layers of consciousness that impede tapping into flow. By knowing the technicalities of any art, we become so proficient that we never have to think about the steps involved. We surrender to inspiration, and the mind opens to possibilities that allow us to create in real-time. That is the splash of enlightenment—the glow of spontaneous creativity that gets everyone’s attention.

Using fMRI, improvisation has become a hot topic in neuroscience, as the researchers’ study one of the most complex forms of creative behavior in real time. They study freestyle rappers, using fMRI scans, for the same reason—they both involve spontaneous works where revision is impossible. Researchers have found that their brains are much quicker and more adaptable. They attribute these qualities to the plasticity (or permanent changes in the brain) wrought by years of practicing.

These researcher’s findings are consistent with the work of music-obsessed otolaryngologist Charles Limb at John Hopkins.

His research found that certain areas of the brain, including regions involved with the senses, activate during improvisation, producing a genuine state of heightened awareness. Trained musicians hear music almost like a second language. The brain patterns during improvisation also resemble those observed during REM sleep, the state of dreaming.

Equally fascinating, certain brain regions are shut down. In every experiment I’ve done where there is some sort of what we call a “flow state”—such as jazz improvisation or freestyle rap, where an artist is generating a lot of information on the fly, spontaneously—there appear to be important areas of the prefrontal cortex that are turning off, or relatively deactivating. The interesting thing here is that the brain is selectively modulating itself to promote novel ideas and to prevent over self-monitoring and inhibition of one’s impulses. 8

When the musician is in the zone, the ego subsides, and he loses his sense of self. Notes and rhythms burst forth from his instrument faster than the musician can process what he is doing. This same pattern occurs in REM sleep. Both produce unplanned associations and lack of control—both seem like an “other worldly experience”.

Limb doesn’t believe that human society can survive without creativity. He believes that “artists are much closer to the truth,” than are scientists. He continues, “To me, both music and medicine deal with life at its core…. They’re both there to define the essential human condition, to help us understand what it means to be human.” 9

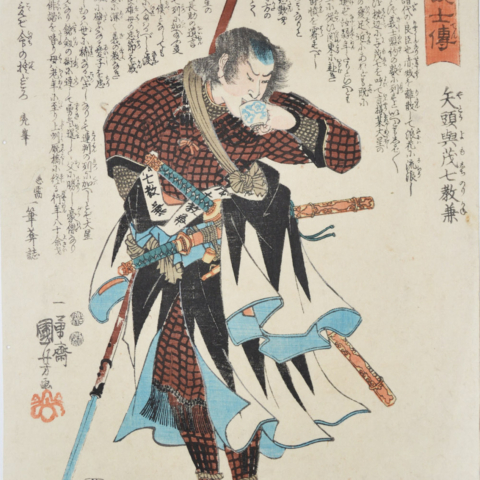

Figure 11.1, Kuniyoshi, Yatio Yomo Schichi Norikane, 1847, Woodblock Print, Ronin Gallery, New York

Chapter Eleven

The Unfettered Mind

“The intuitive mind is a sacred gift, and the rational mind is a faithful servant. We have created a society that honors the servant and has forgotten the gift.” 1 This quote attributed to Albert Einstein reminds us of those enjoyable moments of living in the flow—those moments when our judgmental mind stabilizes and allows us to follow our intuition.

The unfettered mind is the unrestricted mind that lives the middle way between the extremes of indulgence and self-denial. It allows us an opportunity to live a democratic, improvisational life like the musicians recording the Kind of Blue album. We have, within us, the ability to do that by honoring the intuitive mind and trusting life itself. It is a matter of tabling egos for the good of the group. Any time an ego steps up to “defend itself”, the harmony stops as the mind becomes stuck in that place where both attachments to beliefs and suffering are upheld.

Buddhism calls the unfettered mind the abiding place and recognizes it as the sacred gift. During the Muromachi Period (1338-1573), the samurai culture produced the Japanese arts of the Tea Ceremony, Ikebana, and the second wave of Japanese Calligraphy. This form of writing was mostly pursued by Zen monks based on Zen insight; different from the classic Kaisho technique. With the advent of these arts, the martial artists (the Samurai) recognized the need to retrain the mind to keep them in this abiding place, as it was a matter of life and death.

Takuan Soho wrote the earliest essay on training the mind named The Unfettered Mind: Writings of the Zen Master to the Sword Master. In the “Mysterious Record of Immovable Wisdom: The Affliction of Abiding in Ignorance” he wrote,

Although you see the sword that moves to strike you, if your mind is not detained by it and you meet the rhythm of the advancing sword; if you do not think of striking your opponent and no thoughts or judgements remain; if the instant you see the swinging sword, your mind is not the least bit detained and you move straight in and wrench the sword away from him; the sword that was going to cut you down will become your own, and, contrarily, will be the sword that cuts down the opponent. 2

Zen Polymath Soho (1573-1645) sought to infuse Zen in every aspect of his life, including gardening, Teaism, poetry, writing, calligraphy, and fine art. In his essays to sword master and sensei Yagyu Munenori, Soho describes using this state of flow in martial arts to save the lives of those that lived and died by the sword. The ancient Samurai rigorously retrained his mind to reach the state of Mushin (a quietened mind), essential to survival. He reached this state by allowing his natural instincts to take over while his egoic mind faded into the background. The guiding factor, the intuitive mind, instructs the rational mind to find intelligent responses. And it lets go of absolutes to create stability and eliminate stress. It allows divergent thinking needed to make fair and sensible decisions. By staying in the present, he can act decisively and with clarity of mind, much like standing in the eye of the storm. Information in this stage reaches the brain at over 11,000,000 bits per second, making these steps effortless. These practitioners reported that fighting became a joyous artistic performance, as it allowed for a sudden appreciation. By letting go of control, the warrior understood his connection to the world. Soho said, “Completely forget about the mind [ego], and you will do all things well. But, on the other hand, if you do not completely discard the mind [ego], everything you do will be done poorly.” 3

In other essays, Soho encouraged the swordsmen to not limit flow to only martial arts—the aim is to attain the same level in every aspect of his life. They knew to never confuse knowledge with experience. Reaching effortless effort is a trust in the innate instinct rather than the rational mind. In the last essay, Soho talks about the traits necessary to become a worthy member of the samurai community. Through a code of honor, these warriors served as military nobility and stood as examples for the rest. As Soho wrote, “A person may be as eloquent as a rushing stream, but if his mind has not been enlightened and if he has not seen into his own true nature, he will not be someone to be relied upon. We should be able to discern this quickly from a person’s behavior.” 4

When we practice martial arts, or any other act of improvisation, it is imperative we live the middle way—in balance with the Yin and Yang. It is an understanding of how to refrain from any action that will prove harmful—it is in harmony with life’s natural forces. Without the balance, the “martial” may outweigh the “art”. By creating a holistic experience that is even-handed, without prejudice, we can find the orchestration we are looking for.

This underlying philosophy of martial arts remains as significant today as was in the 17th century when it was written because it still emphasizes the understanding of fear and self-understanding. Both are still at the root of human conflict. To live the middle way, we let go of absolutes—and we notice the silence in the sound and the space in the form. We know what to do and how to do it. We know the world is workable. Finding this state is what the Zen Buddhists call No-Mind or Mushin. It allows us to acknowledge our sacred gift and work with our rational mind in the flow.

Our conscious minds delude us about reality. Freud considered this part of the mind, the ego, to be the seat of anxiety responsible for initiating conflicting demands and instinctive impulses and withstanding the superego’s perfectionist squabbles. The end of suffering is to bring about clarity by noting these thoughts without attaching an emotion to them and redefining the freedom to move beyond them. Most people live their entire life within the small confines of the ego. They have not learned to use their thoughts for their own well-being. Therefore, they only experience a fraction of what life offers. Scholar D. T. Suzuki explains this phenomenon. “The ultimate standpoint of Zen, therefore, is that we have been led astray through ignorance to find a split in our own being, that there was from the very beginning no need for a struggle between the finite and the infinite, that the peace we are seeking so eagerly after has been there all the time.” 5

Most people consider themselves experts in some field, but we are only experts in a particular style (the one they taught us). We adopted a philosophy of beliefs based on what the status quo exposed us to without exploring other ways to look at the same thing. As the ego continues to grow, it blocks the information that disagrees with what we learned and yields to the information that confirms our collections of memories and beliefs. We think we are learning, but we are steamrolling through information and conversations, waiting until we hear something that matches up with our current ideas or former experiences, to qualify our beliefs as “right”. We become slaves to these belief systems without realizing it, because we never appeal to the humanity of those we disagree with.

Free from attachment to the ego, South Korean Zen Buddhist monk and temple cook, Jeong Kwan, approaches cooking as communion and as meditation. She explains Mushin this way, “Creativity and ego cannot go together. If you free yourself from the comparing and jealous mind, your creativity opens up endlessly. Just as water springs from a fountain, creativity springs from every moment. You must not be your own obstacle. You must not be owned by the environment you are in. You must own the environment, the phenomenal world around you. This is being free”. 6

Eric Ripert, chef at Le Bernardin in New York City, talks about Jeong after meeting her to study Korean temple cuisine.

Being with Jeong Kwan has been a very special experience for me. I learned, of course, techniques that I didn’t know… flavors that I’ve never tasted before, ingredients that are foreign to me. But her influence is more philosophy than the techniques. Her philosophy is Buddhist philosophy. It’s about being in the present. It’s about respecting the ingredients… the planet… making people happy… how to be happy in the process… how to put good energy into the food. It’s all of that. That is the big change in my life. That’s the influence of Jeong Kwan. 7

Writer and editor Jeff Gordinier met Jeong Kwan at Le Bernardin and then visited her at her temple at Chunjinam Hermitage. This is his recollection of his visit.

And this seems like the most Zen idea of all: that one of the world’s greatest chefs can often be found mapping out her meals in silence and solitude, plucking mint leaves in a garden that feels far, far away from anything resembling preening egos and gastronomic luxury. But she seems to know that positive energy has a habit of finding its way out into the wider world. One day, after we had toured the temple, she led me down to a small bridge that crosses over a creek. We stand on the bridge, and she touches her hand to her ear. She wants me to listen. So, we listen. She and I simply stand there by the water for a couple of minutes, listening to the sound of the current. Then she smiles—it really is like a ray of light, this smile—and points to the creek and utters a single word in English, as she looks into my eyes. ‘Orchestra,’ she says. 8

Meditation is the only way we recognize our thoughts as espoused by the ego. The memories that float around in our mind could not come from inspiration. Once we allow them to bubble up on their own, we recognize them without empowering them with emotions. They will dissipate on their own and our preoccupation with self disappears. Curiosity, mindfulness, and meditation take us deeper to recognize our fundamental nature. Through Mushin, we reopen to the state we knew in the beginning—a quiet wisdom that stays in the present. Without ego, delusions disappear, and we are aware of a mind ready for anything and open to everything. Essentially, we live in a state of flow. With a mind free of discursive thought and judgement, we are free to act and react without hesitation. Relying on instincts, the mind works at a very high speed and without intention, plan, or direction. We become part of the orchestration of life by living in the state of flow 24/7.

Whether we are in a studio painting, a dojo doing katas, or just living in a state of inspiration, surrender, or flow, is the optimum performance mindset. Flow is something we allow to happen and not the result of exterior events. It is our ability to focus and gives order to our consciousness effortlessly. We also know this state of mindfulness as the unfettered mind. It is an altered state of time—a meditation that never stops. This is where awareness lives, and divergent thinking offers an array of possibilities so that we can perform spontaneously in real-time. In “Bushido, The Five Spirits of Budo” Dr. Bohdi Sanders writes, “The Japanese say that Mushin cannot be understood with the intellect, but that it must be experienced. And that is true. When you go into Mushin, your mind is quiet, but your body is acting. To achieve this state, your mind must be free from any conscious thoughts, including anger, hesitation, doubt, fear, or thinking about how to do what you are doing. You simply act. You allow your spirit to guide your body.” 9

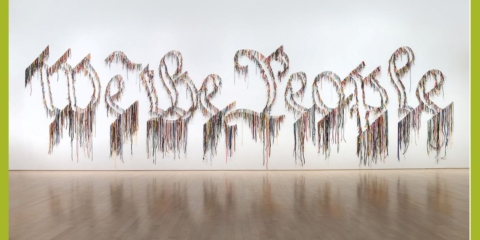

Figure 12.1, Rashid Johnson, Untitled Anxious Red Drawing, 2020, Hauser & Wirth, New York

Chapter Twelve

The Royal Road

All humans are born with the entire history of humanity’s inventions in their unconscious mind. And he was born with the ability to create a life of his own design to perpetuate evolution. We can never lose this ability—it is who we are. Creativity happens in collaboration with conscious and unconscious manners and is the most important tool in solving today’s problems and adding to the collective unconscious.

The human mind has four tiers: the conscious, subconscious, unconscious, and superconscious. The conscious mind is only the tip of the iceberg (roughly 5%) and the subservient part of the mind. It understands the five physical sensory tools, and it includes feelings, thoughts, and actions in the current presence. It averages only 40-50 bits of information per second and is only concerned with activity. There is no stored information. The subconscious accumulates memories, including the ego, and the conscious mind communicates directly with it for information.

The ego is the sum of our beliefs collected since early childhood. These beliefs help define who we think we are. The problem is that many of these beliefs contradict each other, as they are a combination of childhood observations and socialization. The ego operates like a default program which functions automatically. Buddhism’s proclamation that all men suffer is based upon knowing how the ego directs our thoughts. The Buddhists call it the monkey mind—the constant chatter of the ego. This untrained thinking imprisons us in fear and produces a constant personal survival mode. People and situations with similar beliefs are drawn to this fear-based thinking thereby creating the status quo. This perpetuates a society with the same old selfish habits at the expense of a higher civilization of kindness and collaboration.

The ego creates random thoughts that enter existence in a random chaotic way—creating an inaccurate picture of reality and the mind itself. As we search for certainties in life, we label people, experiences, and objects. As a result, we live in a dream world and carry illusions disguised as “beliefs” about other people and ourselves. To end suffering, bring about clarity, and allow flow, we need to become familiar with our patterns. When we are uninspired and following mindless behaviors that no longer serve us, we need to consider retraining. Life is a limitless process of change, and there are no certainties. By acknowledging “beliefs” objectively, we disempower them and let these patterns go, allowing us to live a more authentic life. Through meditation and mindfulness, we can separate these thoughts and recognize them as impotent, having nothing to do with reality. Without these “beliefs” and judgements, we live an awakened life.

95% is the sacred gift and the dominant part of the mind. The unconscious (about 30-40%) and subconscious (about 50-60%) control attitudes, beliefs, habits, and behaviors.

The subconscious lives in the eternal present and is very literal (there is no past or future). It has no capacity to discern truth from falseness and acts upon demands of the conscious mind. This part of the brain processes 11,000,000 bits of information per second on average and communicates through feelings, emotions, imagination, and sensations. The subconscious handles homeostasis and guides the autonomic nervous system to protect us both physically and emotionally. We could not sustain life without it—it develops patterns associated with survival and evolution.

The conscious mind turns off with sleep, but the subconscious never stops. In the dream state, the subconscious works with the unconscious. Instincts occur as we draw upon patterns collected in memories. These revelations induce the complete but temporary suspension of the ego’s doubts and fears. When epiphanies unite with the subconscious in the conscious state, we reach our best decisions. Current habits, such as daily meditation, writing routines, and painting, lock into the subconscious and become a permanent part of our daily behavior. The subconscious conditions our behaviors through our attitudes, beliefs, and habits. It stores our current memories, which are accessed at will. But it denies access to its restrained contents and deeper instincts found in the unconscious. With the practices of mindfulness and meditation, we awaken the deeper potential of the subconscious mind. And only through retraining our subconscious can we gain access to unconscious content.

The unconscious is holistic and influences everything we do—it is the source of all the programs our subconscious uses, soaking up everything without analysis, criticism, and judgement. It can sort through layer upon layer of information. While our subconscious mind searches for answers to questions, it’s the unconscious mind that finds them. Our unconscious awareness works in our intuitive side, the right hemisphere of the brain. In non-verbal contemplative practices, such as yoga, daydreaming, meditation, the martial arts, and Shinrin Yoku, we extract sustained awareness rooted in the unconscious. By focusing our attention on the present, we suspend linguistic consciousness, allowing our unconscious resource to unfold. It is capable of simultaneous thought and action—as in improv—as in flow. These resources, with their intuitive reasoning, bring us the arts of music, imagery, healing, and humor. As translated by D. T. Suzuki, Chan Buddhist monk Shen-hui explains, “Those who see into the Unconscious have their senses cleansed of defilements, are moving toward Buddha wisdom, are known to be with Reality, in the middle Path, in the ultimate truth itself. Those who see into the Unconscious are furnished at once with merits as numerous as the sands of the Ganges. They are able to create all kinds of things and embrace all things within themselves.” 1

Jung believed that we, as a species, have an inflated sense of our own importance. That we have experienced the limits of our present evolutionary path and that we cannot evolve further through our consciousness. He concluded, “The discovery of the unconscious means an enormous spiritual task, which must be accomplished if we wish to preserve our civilization.”. 2

According to Jung, we can divide the unconscious into two layers. The personal layer is a reservoir of deep-seated material gathered since birth. We gathered all experience in the subconscious mind, eventually becoming forgotten or suppressed, and filed into the unconscious. This filed information includes implicit knowledge. Together, they form our personal wisdom made of our experiences, insights, and intuition. By tapping into this wisdom, we can build self-esteem by repurposing experiences that have held us back. It builds empathy for us and all others as it is an understanding of the one-way humans suffer. This self-esteem helps with our self-guided education and self-actualization. As we continue to grow, we gather and file experiences 24/7 in the unconscious mind.

The second layer is the collective unconscious, also known as the superconscious, which contains the accumulation of inherited psychic structures and archetypal experiences, which are not memories but energy centers or psychological functions apparent in the culture’s use of symbols. The superconscious represents intuitive and inspirational creative thinking. It is spiritual wisdom and is outside the box. The mechanisms of this holistic brain activity relate to long-term memory and processes information at the rate of 10300 times faster than the conscious mind. And it processes images in 40-50 milliseconds.3 As Jung describes it, “The collective unconscious contains the whole spiritual heritage of mankind’s evolution, born anew in the brain structure of every individual.” 4 It is a well-spring of beneficial information via intuition, dreams, inspirations, creative ideas, inner guidance, and visions. Sometimes this information reveals itself in bits and sometimes as complete packages—as in Mozart’s finished scores.

The hippocampus plays a major role in learning and memory and is vulnerable to external factors like stress, drugs and alcohol, and unfavorable environmental changes. Under these reduced versions of mental activities, insights, ideas, and concepts are impossible and adequate solutions are unlikely. A society in which these conditions are dominate and creativity is deficient, has no future.

Transforming the subconscious into a directorship tool allows information from the deepest parts of the unconscious to become available. We cannot directly communicate with it, but autosuggestion, rumination, and positive thinking are tools. To program the unconscious mind for specific information from the collective unconsciousness, we literally sleep on it and allow the unconscious mind to answer our inquiry. In the early theta hours, our information will be waiting for us. In an interview, Canadian filmmaker, director, writer, artist, and engineer James Cameron describes how he gets a lot of his ideas from dreams. He describes it as receiving visions with metadata describing the image. For example,

The Terminator was based on a single image of a chrome skeleton emerging out of fire. But the metadata said it used to look like a man covered in flesh and the fire burned it away. And so, it’s actually a story segment. And you start putting those story segments together and then it starts to turn into a story you want to tell other people. I think storytellers sitting around the campfire in a cave 50,000 years ago were doing the same things. 5

Through a deeper understanding of ourselves and these various practices, the impossible becomes possible. The unreachable and unknowable part of our unconscious can be retrained and the power of the superconscious harnessed. By tapping into this collective unconscious, Cameron discusses Avatar,

I try to tap into universals of human experience. It’s about that universal sense of who we are as human beings. If you think about it in a broader sense, that’s how the Avatar movies work. They ask us to see through the eyes of nature, through these blue people back at ourselves and our sins against nature that we collectively as a civilization are doing.

I think maybe one in a thousand people that go to an Avatar movie actually roots for the humans. But we’re a human audience rooting against ourselves through these aspirational characters that really represent the best of us or the way we imagine we can be or maybe the way we used to be thousands of years ago. 6

Psychoanalysts have been interested in art as expressed in the unconscious mind and they have examined artistic impulse—the factor underlying creativity. Art therapy can uncover personal wisdom just as psychoanalysis can. It’s a question of seeing the creative process as a process of self-discovery. As breathing perpetuates our physical life, thinking perpetuates our evolution through our ability to create. Art making allows meditation to take place in the present moment and to cultivate an awareness of thoughts and actions. All the senses and the physical body use art as the transitional technique to bring ideas, beliefs, or phobias from the unconscious mind to the conscious as they are. These kinesthetic and symbolic opportunities circumvent the limitations of language and give voice to experiences that empower transformation of the self and empower society.

During our imposed shutdown during the COVID-19 pandemic, I ran across a red painting (Fig. 12.1) that expressed the stress I was feeling. The multidisciplinary artist wrote the attached article. Rashid Johnson said,

Anxiety is part of my life. It’s something that people of color don’t really discuss as often as we should. It’s part of my being and how I relate to the world, and being honest with that struggle has been rewarding for me. It has led to the kind of self-exploration that produces fertile ground for my output as an artist.

I needed a cathartic release, a way to describe my emotional state. I don’t often make work by responding immediately to a set of circumstances—I tend to kind of take in information and then translate it over time—but this was something that I felt needed to happen quickly. When I began making Anxious Men, I grappled with the aspect of fatherhood. How would I translate the world to him? There was so much happening at the time: the migrant crisis, unending police brutality, the election of Donald Trump. There was the sense that the world was finding itself in a place that seemed frustrating, scary, and dark.

The role of art right now is to not avert its eyes from the crisis and its effects. It’s not a time to be didactic; it’s a time to be present, to be part of the world. That doesn’t mean I think every artist needs to be making new work right now. Artists often wait and observe and gather information and find a way to interpret the moment. I have no expectations for artists other than for them to keep doing what it is that we do best: to be honest about who we are. 7

After writing this article and finishing the series, Johnson said, “Now I feel like there’s an opportunity in the world for peace and for meditation and for a different kind of cathartic resolve”.8 Artists, like Johnson, take their vulnerability and the mastery of their chosen discipline to lay it all on the line. It is their calling that allows them to find deeper realities in which transformation and things of awe happen. They bring light to the collective unconsciousness and show us our universe. The artist knows how to communicate experiences through art, which becomes the portal through which the viewer passes to have their own experiences. Noting this exchange, Freud developed the concept of ideational mimetics. He argued this exchange of energy between the viewer and the artwork was like empathy. “… this experience was a fundamental part of life in higher level civilization.” 9

Art is the ontology shared by all beings in the second layer of unconsciousness—the superconscious. We gain enlightenment by seeing reality as it is—a harmonious state within disagreements and contradictions. Freud recognized a factor in art and literature, which tapped into this layer of unconscious and he called it dream-work.

A piece of art is not only the symbol of one’s unconscious motives but also the expression of many socially undesirable wishes and fantasies, just like dreams. While in dreams, the manifest content aims at concealing the latent thought of the dream, in artistic creation, the ego function has the additional goal of molding thoughts into a form which will be understood. In art and literature, in other words, we find a corroborator of dream work. Like the repressed unsatisfied and unconscious desires are expressed in dreams, similarly, the unsatisfied wishes and rejected feelings are penned in art and literature through various symbols, puns, humours and the like. Just as a dream is said to be the gateway to unconscious, similarly art and literature can be called to be the royal road to the unconscious mind of the artist or poet. 10

Carl Jung agrees. He describes it this way, “The dream is the small hidden door in the deepest and most intimate sanctum of the soul, which opens to that primeval cosmic night that was soul long before there was conscious ego and will be soul far beyond what a conscious ego could ever reach.” 11 The artist is, in the deepest sense, the bearer of the soul of humanity. He is the seeker, the reservoir, and the transmitter of the human condition and the human seasons. Jung described the role of the artist this way: “The specifically artistic disposition involves an overweight of collective psychic life as against the personal. Art is a kind of innate drive that seizes a human being and makes him its instrument. The artist is not a person endowed with free will who seeks his own ends, but one who allows art to realize its purpose through him. As a human being, he may have moods and a will and personal aims, but as an artist, he is a man in a higher sense—he is ‘collective man’—one who carries and shapes the unconscious psychic life of mankind.” 12

Figure 13.1, Brenda Christian Brown, The Journey, 2018, collage of handmade papers. acrylic and oil paints, cold wax on Canvas cradled in teak, 36 x 24 x 1.5”

Chapter Thirteen

Personal Evolution

The reason we’re alive is to express ourselves in the world.

And creating art may be the most effective and beautiful method of doing so.

Art goes beyond language, beyond lives.

It’s a universal way to send messages between each other and through time.1

Rick Rubin

Whereas creativity opens into infinity, the process of inner transformation takes place to excavate the original self. By engaging in the act of creation, without ego, we stay in the present moment and stay open to experiences without prejudice, allowing us to sift through divergent thinking and see things differently than in the past.

Since childhood, I have always been introspective with a heavy dose of curiosity. I would say that I was always intellectually overexcited, concerned with a love of truth and the joy of finding new understandings. Being a perceptive observer, I enjoyed constructive criticism, and was constantly probing for relationships between matter and answers to problems. My respect for man’s creations was equal to nature’s. These desires to know how the world worked led me to the knowledge that the inner world determined my external life. Each of us creates our personal, collective, and interconnected realities. We shape our world by a type of democracy made of this interconnectedness. It is a fact that inner peace is the foundation for world peace.

As we learn to value the gift of creativity, we learn to value the responsibility that goes with it. We can no longer use our ignorance as an excuse to be irresponsible and uncaring. Our scars in life guide us in new and more meaningful ways—to create a thing personal to us, enabling us to create a new thing that has never existed before. Often, these revelations need an explanation from the unconscious, which may take time to understand. It is a riddle that solves itself. By putting a question on the back burner, we allow for incubation and time for divination to kick in.

Realization of a new and unexpected idea is born in a superconscious form, which interacts with the subconscious to the conscious—transcending ordinary consciousness. One way this interaction occurs is by going to the root of the problem through meditation. A virtual reorganization of neural connections occurs in the conscious and unconscious minds once we practice meditation daily. Dr. Andrew Newberg is one of the most influential neuroscientists alive today and is a pioneer in neurotheology, the study of religious and spiritual experiences.

Newberg found that certain areas of the brain were altered during deep meditation. Predictably, these included areas in the brain’s front that are involved in concentration. But Newberg also found decreased activity in the parietal lobe, the part of the brain that helps orient a person in three-dimensional space.

‘When people have spiritual experiences, they feel they become one with the universe and lose their sense of self,’ he said. ‘We think that may be because of what is happening in that area—if you block that area, you lose that boundary between the self and the rest of the world. In doing so, you ultimately wind up in a universal state.’ 2

As we retrain our mind on our journey to self-actualization, we allow ourselves deeper meditations, blissful love, and the unfoldment of the deepest level of the unconscious. This is the creative place where we find inspiration for great works of art, music, prose, great scientific discoveries, and spiritual journeys. In his book, written with the late Eugene d’Aquili entitled Brain Science and the Biology of Belief: Why God Won’t Go Away, Newberg describes this neurobiology:

We believe that all mystical experiences, from the mildest to the most intense, have their biological roots in the mind’s machinery of transcendence. To say this in a slightly more provocative way, if the brain were not assembled as it is, we could not experience a higher reality, even if it did exist.

… no matter how unlikely or unfathomable the accounts of the mystics may seem, they are based not on delusional ideas but on experiences that are neurologically real. Our understanding of brain processes predicts this, and our SPECT scan studies of Buddhists and Catholic nuns show that the meditative, contemplative mind strive in that direction.

What we do suggest is that scientific research supports the possibility that a mind can exist without ego, that awareness can exist without self. In the neurological substance of Absolute Unitary Being, we find rational support for these inherently spiritual concepts and a scientific platform from which to explore the deepest implications of mystical spirituality. 3

Different philosophies, religions, and spiritual teachings call the superconscious by many names. It is the Universal Mind, Higher Self, Internal Teacher, The Source, Buddha Mind and the Collective Unconsciousness. In this book, I have described this connection as enlightenment, Mushin, self-actualization, and described the feeling as levitation above the psychological limitations of the self or group. We witness as we watch performances in flow, when we realize the divinity in our everyday life and know the truth is in us, not somewhere else. We are born equipped to transcend the socialization of the egotistical mind, and in doing so, recreate our original humanity.

This search for the connection I sensed in my newborns, and all infants, seemed to be the same connections I knew in myself now. I was living in the flow. The fears were gone and replaced with tranquility, which allowed me to know peace. Knowing my authentic nature allowed me freedom from thoughts, feelings, and external experiences, leaving me open to magic, fascination, and open-ended learning. Living in the present moment is life-giving, allowing me to stay closer to my core. Spiritual virtues like unconditional love, patience, humility, compassion, understanding, and tolerance came in the package. These qualities appeared on their own without consciously eliciting them. Addictions and attachments drop away on their own—we just don’t need them anymore. Freedom from aversion, dislike, opposition, unhappiness, and restlessness disappeared on their own too. Suffering ended.

During our unfoldment, we realize that the freedom we seek has been with us since birth. The only bondage we know is our own egotistical human bondage of ignorance. There is nothing to aspire to; we have always had what we needed. It is not a case of developing our highest wisdom, but a case of developing ourselves. American philosopher Abraham Kaplan says of Zen “… solution to the great problems of life, is not solving it all: the not solving is really the solving. The wise man does not pursue wisdom but allows it to unfold as he lives his life. Therein does his wisdom lie. The wisdom that Faust comes to in the end, Zen starts with it.” 4

Eventually, we realize that the same way we decide to be happy or miserable, we decide to be more aware or not. We create our lives the way we want. Learning how to count on ourselves, to find the truth, and to respect it allows us to know what a powerful force we are and how important we are to the rest of this earthly survival. We will know ourselves as creators.

Humanistic philosopher, sociologist and social psychologist Eric Fromm describes the human development process this way:

Physical birth, if we think of the individual, is by no means as decisive and singular an act as it appears to be… In many respects, the infant after birth is not different from the infant before birth; it cannot perceive things outside, cannot feed itself; it is completely dependent on the mother, and would perish without her help. Actually, the process of birth continues. The child begins to recognize outside objects, to react affectively, to grasp things and to co-ordinate his movements, to walk. But birth continues. The child learns to speak, it learns to know the use and function of things, it learns to relate itself to others, to avoid punishment and gain praise and liking. Slowly, the growing person learns to love, to develop reason, to look at the world objectively. He begins to develop his powers; to acquire a sense of identity, to overcome the seduction of his senses for the sake of an integrated life. Birth, then, in the conventional meaning of the word, is only the beginning of birth in the broader sense. The whole life of the individual is nothing but the process of giving birth to himself; indeed, we should be fully born, when we die — although it is the tragic fate of most individuals to die before they are born.5

In Fromm’s book, The Sane Society, he suggests that a coherent world encourages its citizenry to grow continually, whereas an insane society discourages ongoing rebirth and provides the individual estranged. Here Fromm explains:

The psychological results of alienation are [that] man regresses to a receptive and marketing orientation and ceases to be productive; that he loses his sense of self, becomes dependent on approval, hence tends to conform and yet to feel insecure; he is dissatisfied, bored, and anxious, and spends most of his energy in the attempt to compensate for or just to cover up this anxiety. His intelligence is excellent, his reason deteriorates and in view of his technical powers, he is seriously endangering the existence of civilization, and even of the human race. 6